Facing Polar Bears, Isolation, Researchers Explore Arctic Sea Ice

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC | Life aboard the icebound R.V. Lance, as scientists study the effect of warming temperatures on the Arctic.

FIRST PUBLISHED IN NATIONALGEOGRAPHIC.COM, MARCH 19, 2015

82.44 DEGREES NORTH—We've drifted across the frozen Arctic for 30 days. Four miles here, ten miles there—a squiggly red line on the ship's digital chart is the only measure of progress.

Trapped in ice, the Lance meanders at the mercy of wind and current. Some days, low, moist clouds engulf the ship from the south; on others, cold northerly winds chill it by 50 degrees. Switched off at this latitude for four months of the year, the sun now rises higher each morning, casting long shadows off surface ice ridges and snowdrifts as it traces a low arc across the horizon.

From January to June, in six-week stints, scientists are on board the Lance, a research vessel operated by the Norwegian Polar Institute (NPI), to study how the ocean, atmosphere, snow, ice, and biology all interact in the Arctic amid a backdrop of significant warming. "Right now we're just trying to take as much as we can, because this is a one-off opportunity to get this data," said Amelie Meyer, an NPI oceanographer. "And nobody's got it."

Isolation has settled in. The Lance is currently some 250 nautical miles from another human dwelling or vessel—farther than the distance between New York and Washington, D.C.

At one point, a polar bear crossed our path, paused for several days to sniff at the weather masts and strange-looking electronic instruments it encountered, and then eventually moved on.

A bioluminescent jellyfish happened by a hole bored in the sea ice one day, drawing excitement: signs of life! The other night, a marine biologist sat elated at her microscope as it magnified a rare glimpse of an amphipod, caught in a net that day from 200 meters (656 feet) below, giving birth to ten offspring.

People refer to life on board as "The Bubble." Snippets of world news leak in through email, via satellite, like communiqués from another planet. What date is it today? Certain things just fade from mind. "It's kind of comforting to not be bothered by all of ordinary life's problems," admitted Algot Peterson, a Norwegian oceanographer. Without smartphones or the Internet, he said, "you actually sit and talk to each other."

Absence of distractions also brings into sharper focus the task at hand.

Each day, worker bees in yellow-and-black jumpsuits drag children's sleds laden with tools and equipment to their study sites across the ice floe. They analyze it from every angle. With a thermometer and a scale, a snow physicist stands thigh-deep in a snow pit, measuring the temperature and density of the different layers of snowpack to discern how much it insulates the sea ice from the cool atmosphere above. A Japanese biogeochemist deploys a robot that traps and measures carbon dioxide emissions off newly formed sea ice, its surface ornamented with delicate bouquets of salty ice crystals known as frost flowers. Nearby, sea ice physicists drill ice cores that they'll analyze for their internal crystalline structure, which holds clues to the environmental conditions under which the ice grew.

Farther below, warm Atlantic seawater, which passes between Iceland and Norway as it enters the Arctic, lies beneath a 100-meter-thick (328 feet) layer of cold surface water. Several times a week, oceanographers send down instruments that probe these layers of seawater to determine how much—and when—they mix, as heat from the Atlantic water influences ice thickness and its extent across the Arctic.

Woosok Moon, a researcher from the University of Cambridge, tries to make sense of all the data. In his cramped cabin on board the Lance, he spends evenings scribbling arcane equations into a notebook, which no one else seems to understand.

Much more than mid-latitude environments, Moon explained, the Arctic sea ice system, especially in the summer, is highly sensitive to any disturbances. As more bright ice melts and is replaced by dark ocean, for example, more solar energy is absorbed in the water, raising temperatures of the ocean and air that in turn melt more ice—a process known as the ice-albedo feedback.But other feedback loops counteract that process. "It's like an unstable person, bothered by neighborhood noise one day, and a gentleman the next. It's very hard to make future predictions about erratic behavior."

Moon is trying to forecast the status of the Arctic sea ice by building a stochastic model, which is similar to the models used to make stock market predictions. It concedes that there are certain behaviors of sea ice that are simply too complicated and too unknown to try to force into a model—how two ice floes located side by side can vary in thickness, for example—but it maintains that with a deep understanding of the basic physics driving sea ice growth and melting, one can narrow the uncertainties enough to make a reasonable prediction.

As Moon sat inside the Lance, 34-mile-an-hour winds swept in from the south. They pushed the ship in the opposite direction of its planned drift back to Spitzbergen, undoing two days of southward progress in a matter of hours. The temperature shot from minus 22 degrees F (-30°C) to 32 degrees F (0°C) overnight, eventually settling back to minus 7 (-22°). The ice floes hemming in the Lance, meanwhile, slowly became unstitched.

First one crack here, then another, the fractures slowly widened until the ship was separated from the various study sites across the floe by gaping channels of exposed seawater, which began radiating smoky vapor. One split took down a 33-foot-high (10 meters) weather mast in the atmospheric science quarter. A GPS station began to drift its own way. There went the neighborhood.

Also, the boat was stuck. The industrious crew spent the next two days trying to dislodge the Lance from nearly 18 feet (5.5 meters) of ice blocks that had nestled under its bow during a storm two weeks earlier. A tranquil week of data collection suddenly turned into an instrument rescue mission. It was time to pack up and abandon the floe—if only the boat could set loose.

Many, naturally, had anticipated such a disturbance. "That's uncertainty," Moon joked.

Dining Room Diplomacy

SALON | As bombs fell on the Middle East, I cooked a gourmet meal for a group of Arab artists -- and between bites of roasted tomatoes and baby lettuce, the world seemed at peace.

FIRST PUBLISHED IN SALON, DECEMBER, 2006

One brisk evening last July, two Jews in Berkeley, Calif., discussed the Tunisian circus with a group of Arab artists over plates of polenta, summer squash and a confit of tomatoes that resembled clowns' noses. The incongruity of the occasion, while fighting engulfed Israel, Lebanon and Iraq, and summer heat blanketed the rest of America, was not lost on the diners. Around the table sat the founder of a clown school in San Francisco, and distinguished guests from Tunisia, Egypt, Qatar and Bahrain, who had arrived by invitation of the U.S government. I was their host.

The scene had overtones of citizen diplomacy. The State Department, among its many missions, is charged with spreading goodwill abroad. Recognizing that this effort is best waged inside the homeland, each year its field embassies handpick hundreds of "current or potential leaders" -- in government, media, education and other fields -- and invite them on a whirlwind tour of America to meet their professional counterparts and experience the country firsthand.

To provide these dignitaries a glimpse into domestic life -- and perhaps, to prove that our culinary heritage is more Wilsonian jambalaya than George Bush freedom fries -- the State Department's International Visitor Leadership Program partners with nonprofit organizations in each city to arrange home hospitality visits with local volunteers. After all, not everyone deserves a black-tie state dinner, but stomachs are a proven route into hearts and minds.

So several times a year my one-bedroom cottage is transformed into something of an international bistro. Last December, I served three reporters from Turkmenistan their national dish, palov, a pilaf with lamb, carrots, currants and almonds. If I could rate my own establishment, I'd say I earned an extra star that night. My guests, appreciative in the way that locals abroad admire even tourists' sputtered attempts at a native tongue, savored the flavors of their home and eagerly demonstrated how Turkmen chefs prepare the dish, mounding rice with the care of a barber sculpting a pompadour. As the evening eased on, we discussed Turkmenbashi, the country's dictatorial leader who has fashioned a peculiar cult of personality. My questions were met with ambiguous, diplomatic reactions. A week later I received an apologetic call from their interpreter: The group, he explained, had been warned the secret police might be tailing them.

A month later I had a more open exchange with the anchorwoman of Shanghai TV, whom I served Sichuan toasted sesame and Napa cabbage salad along with a smattering of Chinese phrases I learned while backpacking through Asia during the SARS outbreak. After a glass of wine, she offered some off-the-record accounts of Chinese media censorship. (The party's ears, she must have reasoned, were safely out of range.) Another evening, in a pinch, I shyly poured "Two Buck Chuck" Shiraz for a prominent Argentine newspaperman who arrived with a hankering for a fine Malbec. "Delicioso," he remarked, as he held up the glass to inspect the wine's legs.

My Middle Eastern guests arrived in July, when the summer's bounty was near peak, and so I decided to offer them a taste of truly local gastronomy. I phoned Chez Panisse, the birthplace of California cuisine, for menu suggestions. Michael Peternell, chef at the cafe, riffed on the possibilities.

Stay away from couscous, Peternell suggested; the risk of presenting an inauthentic version to such discriminating palates was just too great. Instead, for starters, he proposed a salad of Little Gems lettuce, a baby romaine grown locally by Blue Heron Farms, which I could serve with crispy cucumber slices and a creamy avocado Green Goddess dressing. A main course of herbed polenta wedges would follow, mixed with fresh corn kernels, topped with roasted Early Girl tomatoes and grilled seasonal vegetables -- eggplant, summer squashes and cremini mushrooms -- and drizzled with pesto using basil grown in my backyard. For dessert, Peternell proposed peaches, baked with chopped walnuts, butter and brown sugar, and accompanied with vanilla ice cream.

It sounded promising, if laborious. After shopping at the local farmers market, I returned home to dutifully reproduce Peternell's game plan. At 7 o'clock, my aunt Arina arrived, a former clown and stage performer who now uses theater techniques to coach nuclear scientists in compassionate team building. We picked up our visitors, and their Yemeni interpreter, from the train station.

Such cultural exchanges usually begin with the transfer of gifts, followed by business cards. Once, from a Bulgarian journalist, I received a bottle of rose oil; from a senior advisor in Slovenia's education ministry, an embroidered purse. An advisor to the prime minister of Albania once brought a carved statuette of a famed Albanian warrior, which now sits on a shelf next to a pair of traditional wooden dolls gifted by the head of Mongolia's copyright office.

Ahmad, a musician with the Cairo Opera, presented me an engraved glass pyramid from the reopened Library of Alexandria, where he also works as the international liaison. The only other person in the United States who possesses the same souvenir is Laura Bush, he noted, who visited the library last year. Honoring the distinction, I placed the object in the East Wing of my house, a windowsill. I poured glasses of zinfandel, and we migrated into the backyard.

Most visitors coming through the International Visitor Leadership Program have never been to the United States. They arrive, like many foreigners, with a CNN-and-Hollywood-eye view of American society, which can make for an illuminating reality check. Over dinner, my first questions always address these revelations. A visiting Polish journalist once voiced shock over how fat we Americans are, an observation not readily gleaned from the products of America's pop culture factory.

My guests that July night had accumulated some generous impressions: We are very hardworking, helpful and friendly (ironic considering our reputation as foreign tourists), and very ignorant about the world outside our borders. To illustrate how downright American we are, Abdullah from Qatar recounted how he had visited a church in Washington, D.C., earlier in the week, toting a camera, and a couple nearby offered to take his picture "without even having to ask them!" But everyone was surprised to discover that few Americans own passports. Most certainly couldn't name Arab countries on a map. Later in the evening, my comment that Hosni Mubarak was "repressive" elicited a strong reaction: not for my evaluation of the Egyptian president's administration -- which Ahmad flatly refuted, anyway -- but simply because I knew his name.

Whereas Americans are clueless, the Egyptian public "knows everything about the world ... everything," Ahmad claimed assuredly. I thought the widespread belief in absurd 9/11 conspiracies held by this public -- even journalists and intellectuals -- might challenge his assertion, but I held my tongue.

For our collective ignorance about Islam in general, Ahmad blamed American cable news networks for misrepresenting Muslims. I pointed out that unfortunately extremist voices often out-compete the silent, moderate majority on our airwaves. "Yes, yes, you are right," Ahmad said, shaking his head. "It's our problem." The ignorance works both ways, he allowed, and looked forward to enlightening friends back home.

The morning of the dinner, Israel had escalated its devastating bombing campaign against Hezbollah, and Ahmad -- at 35, the youngest in the group -- was impassioned. Naturally, conversation veered toward Middle East politics. "Why are the American people beside Israel, beside Israel ... continuously?" he wondered. America's apparent double standard, reflected in its handling of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and its stance against Iran's nuclear ambitions, frustrated him. "You are the greatest country, and the strings of the game are in your hand," he said. "Just be fair." Most Arabs today, he added, distinguish between the views of the American people and its politicians, much like they do Judaism and Zionism. But if democracy is supposedly working so well here, why can't American citizens steer Middle East policy toward peace?

Ahmad and I could have compared our differing versions of the history of Jews in the Middle East -- but instead we moved inside to the dinner table, where over Little Gems lettuce wedges, we discussed the arts. Earlier in the day, the group visited San Francisco's Yerba Buena Center. Kathloom, a small, loquacious woman and accomplished actress, filmmaker, choreographer, trainer, director and theater consultant to Bahrain's Information Ministry, was blown away. Arts organizations in the U.S. are essentially nonpartisan entities, with dedicated venues and free range on programming. In Gulf countries, the government retains creative control and funding of the arts, and artists must be recognized by various ministries.

The situation is quite different for the Tunisian circus. Ferid, a soft-spoken, chain-smoking, 54-year-old former lawyer, founded the National Circus Theater three years ago with the help of French trainers. Tunisians, it turned out -- especially Bedouins -- love the circus. Most of his funding comes from their ticket purchases; the rest, from a Coca-Cola sponsorship. In turn, Ferid produces four shows a year awash in Coke branding. For these special performances, the artists' costumes -- ordinarily traditional Tunisian fabrics and colors -- are emblazoned with Coke logos, much like an endorsed tennis player. For one televised production, aerialists and dancers resembled Coke bottles head-to-toe, and as he described it, I imagined a bizarre, "Gods Must Be Crazy"-like scene of lithe soda bottles flying between trapezes in the North African desert.

As Chef Peternell predicted, the tomato confit oozed a flavorful, red juice over the polenta and its seasonal vegetable companions. My guests -- whose culinary expectations of America ended at pizza, fast food and steak -- were delighted. Their reactions sounded like a glowing Zagat listing: "Very nutritious ... my husband will have to cook it!" (Kathloom); "Very good" (Ferid, with an approving nod). "Truly delicious and surprising," announced Ahmad (a compliment I later learned was the only praise he paid American food during his two-week visit).

Dessert was served in the living room. Over baked peaches and French vanilla ice cream, we sipped rooibos tea while Ahmad strummed an oud he'd brought, singing traditional Egyptian melodies in the trilling and seductive vocal style of a muezzin's call to prayer.

"Aysh maana sit alinjiliziah hialli bitrouh alintikhabat/ Wal beit howa bassi gadar asit almasriah" -- "Why can British women vote, while ours are holed up in their homes?"

The lyrics were from Sayed Darwish, a prolific composer who, in the early 20th century, championed modernity and social progress during the era of British occupation. His provocative words have a contemporary relevance, of course; in Egypt today, fundamentalism is gaining support, and with it, an intolerance for the arts competes with the thirst for freedom of expression. "If the Muslim Brotherhood were in power, they'd kill me," Ahmad solemnly told us.

For a moment, the music transported us all someplace else -- to a land where the air is warm and inviting, but sadly, too often filled by instruments of war. Sitting comfortably on my couch, Kathloom and Abdullah smiled and joined in a familiar verse. Arina joyfully clapped along. I added notes on my mandolin. And then, from an open window, a chill crept into the room -- a reminder that this was, and could only be, a summer night on the San Francisco Bay.

How Entrepreneurship Is Helping to Save Puerto Rico

ENTREPRENEUR | After Hurricane Maria savaged Puerto Rico, a man named Jesse Levin used what he'd learned as an entrepreneur and applied it to disaster relief. And it worked.

FIRST PUBLISHED IN ENTREPRENEUR, APRIL 2018

When Hurricane Maria raked across Puerto Rico last September with wind speeds of up to 155 miles per hour, it left a path of unprecedented destruction. The storm flattened houses and forests, flooded towns and made hundreds of thousands of people homeless. It knocked out most of the island’s power grid, leaving nearly all 3.7 million residents in the dark, and severed 95 percent of cell networks as well as 85 percent of aboveground phone and internet cables. Eighty percent of the island’s crops were decimated.

Once the hurricane moved on, an all-too-common aftermath unfolded. Local emergency responders became overwhelmed. There was, memorably, public fighting among political officials -- San Juan’s mayor versus President Trump. Relief agencies and volunteers flooded in. People who wanted to help could find long lists of organizations to donate to, though, as is typical after a disaster, it wasn’t clear where the money was best spent. Dollars often flowed indiscriminately.

Ten days after the hurricane, a different kind of responder arrived on the island. His name was Jesse Levin, a 32-year-old serial entrepreneur with close-cropped hair and aviators, and the co-founder of a series of rock-climbing gyms called Brooklyn Boulders. He had no military background, though he had volunteered in past disaster zones and spoke the language of relief -- casually discussing “air assets” and “force multipliers.” Before he arrived he’d made plans to help, help that didn’t necessarily involve the cluster of government agencies and NGOs that were scrambling to advance their operations. “It was mind-boggling,” he recalls now. “There was just completely ineffective communication going on.”

A rented jeep was waiting for him.

Once in Puerto Rico, Levin spent several days crisscrossing the island’s debris-strewn roads, talking to residents, business owners, mayors and policemen. He rarely came across an aid worker or a utility truck. In the media, he’d kept hearing that people were desperate for food and water. But in village after village, Levin encountered grocery stores open and stocked with enough provisions to sustain the local communities. Enterprising merchants had even rustled up generators to keep on the lights. But many customers couldn’t buy anything: Around 40 percent of Puerto Rico’s population depends on food stamps, which require Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) cards to make purchases. With the island’s telecommunications network down, the cards couldn’t be processed. This particular problem didn’t require an intensive governmental effort to distribute food and water. It was just a connectivity issue that nobody else was solving.

So Levin coordinated with Steve Birnbaum, a satellite communications expert he works with, who had arrived on the island a week before the hurricane to prep for the storm’s aftermath. Their plan: to personally buy a bunch of small satellite terminals from Focused Mission, an emergency response business on the island. Levin then worked some local government contacts until he wrangled a helicopter. Among them was Puerto Rico’s chief information officer, Luis Arocho, who came along for a beta test to see if their plan would succeed. Soon this small team was airborne and installing terminals on two grocery store rooftops. They flipped the switches and boom -- EBT purchases now worked. Levin would go on to install 12 more.

The experience was validating. “If the economy is broken in a place, the location can’t heal,” Levin says. But now, functioning EBT machines can lead to more products sold, more employees paid and more shelves restocked -- an economic system revived, and saved from further dependence on FEMA aid. He says the hard costs totaled $33,000, which was ultimately reimbursed by the Foundation for Puerto Rico, and that around $3 million in transactions have since passed through the satellite terminals.

But it was legitimizing on a far larger level as well. Levin isn’t here in Puerto Rico simply to do one-off projects like this. He’s here to advance a concept -- an audacious idea that he calls “expeditionary entrepreneurship.” In essence, it’s disaster relief in the form of entrepreneurship. Governments and NGOs are important, he says, with their standard operating procedures and approaches to administering aid. But entrepreneurship -- not profiteering, but the principlesof entrepreneurship -- can accomplish what those bodies cannot: quick and nimble responses to ground-level problems, and connective tissue between foreign aid resources and capable local actors like grocery store merchants who are often not engaged. The same instincts that help an entrepreneur build a business, in other words, can help them rebuild a region from catastrophe.

Levin explains this to me as we drive past toppled power lines and landslide debris in Puerto Rico’s lush interior mountains. It is mid-January, four months after the storm has passed. “An entrepreneur looks at systems and comes up with creative fixes,” he says. “We start from the bottom up.”

Levin didn’t just dream up “expeditionary entrepreneurship” one day. Instead, he came to it after pursuing two parallel paths: He was an adventurer, and an entrepreneur.

He’s always had an entrepreneur’s sensibility -- that ability to sniff out an opportunity and boldly claim it. As a middle schooler in Connecticut, he launched a guerrilla marketing company called Jesse Levin’s Adrenaline Marketing. (Slogan: “With all due respect, you need a kid.”) He talked the beverage company SoBe into paying him $15,000 and helped promote them at extreme sports events by dyeing his, his friends’ and even his dog’s hair the brand’s hue of green.

During summers, meanwhile, he also attended wilderness survival classes, learning how to build shelters and track animals through the woods. He became captivated by the power of resourcefulness -- how solutions exist all around us. “Survival school informed every facet of my life,” Levin says. “My relationships, how I see things, how I conduct my business.”

After graduating from Babson College in 2007, those two passions continued apace. He moved to Panama, got into real estate, eventually bought a farm, and then launched a consulting firm. A Dutch company hired him to do project management and cultural mediation work in a remote coastal area where it had acquired land. The area -- a haven for narcotraffickers and local mafia -- was prone to flooding, and Levin inadvertently became the go-between for the special maritime police and the Red Cross to deliver medical care and supplies to his local community. The experience got him interested in disaster relief, so he followed the typical path: He volunteered. Following the historic earthquake in Haiti in 2010, he joined the NGO Hope for Haitiand spent six months crawling around the rubble. After the 2013 typhoon in the Philippines, he split his time between Manila and a town named Tacloban, where he worked alongside Team Rubicon, a relief organization made up of veterans.

Amid these overseas excursions, he was also pursuing traditional entrepreneurship. He became co-founder of Brooklyn Boulders, a New York climbing gym that was expanding into new cities. The first location was just outside Boston, and Levin’s goal was to draw people to the space. He realized that the same principles he’d learned in Haiti and the Philippines -- drop in with no agenda, assemble a capable operational team and work closely with locals to find culturally relevant solutions -- could work here as well. “We found the bike builders, the finger painters, the VCs and the nonprofits, and as we built, we said, ‘Here’s our philosophy: How can you leverage this space to amplify what’s going on here locally?’ ” Soon the place became a hybrid gym/community center/co-working space, hosting drone races, TEDx events and nude drawing classes, with MIT engineering students mingling with graffiti artists. Levin would replicate the concept in Chicago, and sell most of his stake in 2016.

Throughout this period, starting in 2010, he also launched and ran a company called Tactivate, which pitches itself as a project manager inspired by the strategies and tenets of Special Operations. Through his disaster work, Levin had befriended many Air Force pararescuemen and Army Ranger types. He found them to be inherently entrepreneurial, but their resourcefulness, wide-ranging capabilities and “operational mentality” often went unappreciated in the civilian world. Tactivate could bridge that divide, he reasoned, by combining military veterans with what its website describes as “installation artists, hospitality gurus, bootstrap entrepreneurs, branders” and more, for whatever project needs doing.

That’s turned out to include running events, art installations and a “pop-up outdoor survival training bar” in Miami. His parallel life pursuits had begun to bleed together, each informing the other. In entrepreneurship, he was channeling disaster relief -- the idea of moving quickly, identifying needs and bringing people together. In disaster relief, he’d been applying entrepreneurship -- dropping into post-disaster environments and creatively supporting local capacity.

Along the way, Levin had assembled a vast Rolodex of relief operatives, from medics, communications specialists and private pilots to people involved in emergency logistics and air freight transport. “We all just kind of team up and see how we can fix things,” he says. “We’re fixers.” By last year, he’d come up with the phrase “expeditionary entrepreneurship” as a way to formalize his approach to disaster relief. Now he wouldn’t just be freelancing his way through regions; he’d be enacting a named strategy, which he could communicate to others.

On September 20, this new phrase had its first test case: Hurricane Maria hit.

“Cómo estás, señor!” Levin says, as he bro-hugs the guard at the security desk.

“Todo bien, caballero,” replies the guard chummily.

We’re breezing into La Fortaleza, the bright-blue governor’s palace in San Juan’s colonial quarter, as if Levin didn’t just land in Puerto Rico for the first time three months earlier. We head across the lobby’s marble floor and up the stairs to the corner office of PRITS, or the Puerto Rican Innovation and Technology Services. It’s a newly formed unit headed by two former executives -- Luis Arocho, the island’s chief information officer, and Glorimar Ripoll, its chief innovation officer -- and tasked with introducing data science and technology into Puerto Rico’s bloated bureaucracy. It’s also become something of a home base for Levin, a place receptive to his particular brand of entrepreneurship.

As we approach, we find the office in a flurry of redecoration. A black love seat, armchairs and gold side tables form a new reception area by the door. We stand and watch long slab tables crafted from trees felled by Maria -- and a large wooden PRITS sign emblazoned with the Puerto Rican flag -- being hoisted into an open window by a cherry picker. A giant, flashy canvas donated by a famed local artist, painted with the words La Gran Fiesta, is carried in and then promptly taken away: too much. Levin smiles.

In his vision, everything is scalable -- every relationship, every idea. You start with one thing and build off it. It’s not always easy to draw a straight line from one to the next, but what’s happening in this office, at least, offers a useful pathway of how Levin’s philosophy unfolds.

It started with that project to install satellite terminals. Originally, Levin had asked Arocho, the chief information officer, for help. “I thought, This is great, but knowing government, it probably won’t happen as fast as we need it,” Arocho recalls. It had taken six weeks to request and launch Google’s balloon-powered Project Loon internet service on the island. But when Levin and his team produced the technology in less than a week, Arocho was impressed. “At that moment, I knew these guys were for real,” he says. “They’re forward thinkers. They offer a different approach -- that entrepreneurial mindset -- to dealing with government problems.”

Now Levin had a useful new relationship. Arocho became willing to provide, as he calls it, “top cover” for his efforts -- signing forms when necessary, opening doors. And meanwhile, Levin was repeating this process with other key players around Puerto Rico. He’d befriended the heads of the Foundation for Puerto Rico, as well as key officials from FEMA, the military and the Department of Homeland Security. Leveraging his network, Levin often just connected dots. A cutting-edge, solar-powered water-purification system was installed at a Boys & Girls Club in the town of Loíza because of an introduction Levin made between MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory and the Roddenberry Foundation. He introduced Global DIRT, a disaster response team, to a local organization in St. John requiring assistance, leading to a major response and connectivity operation benefiting the U.S. Virgin Islands. “This connection was immensely valuable,” Devin Welch, a solar-power-business owner, told me.

Direct relationships and one-off operations can only scale so much, Levin knew. What he needed was to re-create what he had with Brooklyn Boulders -- that gathering point where infinite other relationships could thrive and people could find new ways of helping the island. “Whether in business or disaster response, informal relationships are how everything gets done,” he says. So, not long after arriving in Puerto Rico, Levin took over a six-bedroom house near the beach in San Juan that he found on Airbnb. At $275 per night, it came with a bar and an outdoor pool yet cost the same as a room at the nearby Hyatt. Then he invited everyone he’d met for regular Thursday happy hours (but also almost any time), offering a retreat where exhausted relief workers could decompress over cheese, crackers and bottles of Medalla Light, and even crash in a bedroom if necessary. Here, he believed, the silos of NGOs and government and military could break down.

Arocho became a regular. So did senior officials from the U.S. military and FEMA, Puerto Rican bureaucrats and businesspeople and private-sector technology specialists. Smart, young Puerto Rican doers arrived and began working out collaborations with PRITS. A filmmaker hired by AARP showed up and found people to help her document Maria’s impact on the elderly. Members of relief organizations swapped insights, and found partners for their work ahead. “We were better prepared for what was to come during our time there by hearing real stories of what was occurring and needed,” says Tamara Robertson of Engineers Without Borders.

The house created new relationships, but it also continued to strengthen Levin’s existing ones. And that’s how, last January, Levin came to suggest that Arocho redesign the government office. If PRITS is to be an emblem of collaboration and make Puerto Rico attractive to innovators, he argued, the space ought to look the part. Arocho agreed; the office was originally nothing more than a drab, government-issue space. So Levin found a sponsor to put up $15,000, linked in a California-based furniture designer named Marcus Kirkwood and enlisted Levin’s twin sister, Sefra Alexandra, who had also come to Puerto Rico after the hurricane and built seed banks in 26 schools across the island.

Now, on this day in January, we’re watching the fruits of collaboration and relationships. The new tables are being arranged. Sefra is decorating the room with tropical plants. Arocho stands by Levin and looks on happily, snapping pictures.

Much of the attention on Puerto Rico’s hurricane response has focused on government’s colossal failures: FEMA’s sluggish response. The island’s struggle to get a handle on the situation. Corrupt utilities and local mayors. Mismanagement and dysfunction. Wastewater systems and an electrical grid left vulnerable after years of neglect.

But there’s another story: how Puerto Rico’s citizens took care of themselves. Neighbors banded together. They shared food, fuel and shelters, driving their own hyperlocal response efforts. Levin talks about Alberto Delacruz, a Coca-Cola distributor he met who mustered 2,000 generators, loaded them on his fleet of trucks and delivered them to stores, clinics, salons and restaurants across the island. “Yes, he wanted his clients back in business,” Levin says. “But he solved a problem.” Necessity also inspired D.I.Y. solutions. I heard about residents powering homespun washing machines with battery-operated drills that they charged with solar panels; about electrifying their homes with car batteries. Local businesspeople began talking of themselves not just as merchants or salespeople but as sources of solutions -- as linchpins of their communities.

This is, it turns out, a regular though less reported part of the disaster-recovery cycle. “History has shown that the disruption of existing traditions, policies and structures can create a climate of innovation and entrepreneurship,” reports a 2017 study in the International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research. The research was put together by two DePaul University professors who surveyed decades of reports on how entrepreneurship rises in areas that fall victim to disaster. Their conclusions: Perceptions of entrepreneurship always improve as local people, with their deep knowledge of their community’s needs, become effective in ways that large institutions like government can’t. And local entrepreneurs themselves go through a transformation, shedding anxieties that might have held them back before. “Necessities of the individual and his community override increases in fear of failure,” the DePaul writers report. From this, new solutions are created and new businesses are born.

(This phenomenon extends to Levin himself: The co-directors of the University of Delaware’s Disaster Research Center tell me that, after disasters, independent people often step in to do what he does -- help forge connections. They just don’t typically think of themselves as entrepreneurs.)

However, something is happening in Puerto Rico that the DePaul writers hadn’t chronicled elsewhere. Entrepreneurs from outside Puerto Rico are arriving with vigor. Within days of the storm, scores of technology companies in particular have made landfall, ranging from large entities like NetHope and Tesla, which is launching new battery projects on the island, to smaller makers of passive water collection and purification systems and “mobile ad hoc” wi-fi networks. Many see the island as a test bed for their new technologies. Wealthy cryptocurrency entrepreneurs have arrived en masse, eyeing Puerto Rico’s generous tax incentives, broken systems and humbled government as an exciting set of challenges. “It’s turned out to be this really amazing opportunity to put to work block-chain technology,” Reeve Collins, cofounder of the company BlockV, told me.

Levin watched this happen on the island, and two months after the hurricane, he felt it was time to move on to a new phase of his expeditionary entrepreneurship project -- away from disaster relief, and toward disaster preparedness. (Hurricane season begins in June.) He’d now play superconnector for this new community on the island, locals and newcomers alike, whose products and services could help Puerto Rico in the long run.

By this point, Levin had stopped renting his communal Airbnb; the aid workers who frequented the house had largely left. Now he makes connections on the fly. “I go into an area and try to identify who’s who. And I try to empower them and connect them around a goal,” he says. Over the course of my three days with him in January, this is almost entirely what I witness Levin doing. He meets with property developers and investors and lawyers and local foundations and youth activists and surfers and (of course) cryptocurrency entrepreneurs. We stopped in at a tech accelerator one morning to meet re:3D, a startup experimenting with an industrial 3-D printer to fabricate storm-ravaged stuff like furniture and coral. We had lunch with Milton Soto, an influential bartender who is rehabilitating an elementary school after the hurricane, before stopping by Aqui Se Puede, a watering hole whose owner and resident carpenter once worked for Andy Warhol. For Levin, these encounters are mostly soft touches -- rapport building, part of his overarching effort to piece together a network of “local capacity” in the event of another disaster.

One morning, I join Levin for a 7:45 a.m. workout on the beach with Carlos Guardiola, a well-connected Puerto Rican entrepreneur who owns one of the island’s largest warehousing businesses as well as medical cannabis licenses; Rafael Ortiz, who is in private equity; and Ben Manning, a former Navy SEAL fresh out of eight years in the service, whom Levin had taken on as something of an apprentice. (Each night before bed, Levin and Manning “debriefed” about the day’s meetings and exchanged the lessons learned.)

After burpees and sprints, we sit down for breakfast at a beachfront inn.

Guardiola describes his role as an unofficial connector. “I have a very simple rule: I don’t do business with anybody unless I eat with them seven times,” he tells Levin. “I like to see how you treat the waiter. I like to see who you know around. I like to see how you react. Because everybody’s a great first date.” Since 1996, he’s frequently hosted invite-only salons that bring together venture capitalists, housewives, street artists -- an intentionally diverse mix -- and after the hurricane, that made him a natural contact point for many people on the island. Not unlike Levin, Guardiola began making connections that helped the disaster recovery along. In one case, he connected GivePower, a major clean-energy nonprofit, to local partners to install water desalination and purification systems.

“And that’s how real recovery happens,” Levin says. “It’s understanding the landscape, and making very unconventional, strategic relationships of human capital, and understanding the capacity of respective operating groups, and putting them together.”

“It basically comes down to what we’re doing here -- it’s breaking bread,” Guardiola replies. “I’m not in the business of employing people, because I think that’s what kills Puerto Rico. That whole mindset of I want to get my sure thing. There is no such thing as a sure thing! And that’s why this is really the perfect storm. You know everybody was thinking, Oh, the United States, they got our back. Bullshit! Oh, we’re going to get money from FEMA. Bullshit!”

If Puerto Rico has a savior, they agree, it will be the entrepreneurs on the island -- both the ones born here and the ones flocking in. This is the lesson they took from Hurricane Maria. “Once you realize that no one is here to save you,” Guardiola continues, “that is the most empowering thing, or the most frightening thing. And whoever is frightened should get on a plane and go to Orlando. Get the fuck out of the way.”

One day, before a meeting with a lawyer from a prominent Puerto Rican real estate family, Levin takes me to the ruins of the former Naval Reserve Officers Beach Club. It’s perched over the sea, above a popular surf spot and in the shadow of an old Spanish fort, but it’s an absolute mess: small buildings stripped down to the concrete and covered in graffiti, hunks of wood scattered like discarded toys. The site belongs to the city of San Juan, but he’s actively courting the city government and pitching investors to turn it over to him.

Here, Levin says, is where he can have a truly lasting impact.

“I’m proud of our ability to drop in and be operational, but really, at the end of the day I’m just another guy going out and fixing a radio, or clearing search and rescue,” he says.

That’s why he wants this permanent space -- a place to once more repeat what he learned at Brooklyn Boulders. When he’d bring the climbing gym to a new city, Levin would start by inviting a diverse group of locals -- from investors to artists -- into the space as they were building it. He called the gatherings “hard hat dinners,” and the goal was to get influential constituencies in the community to meet each other and have a say in what became of the space. That way, when it opened, they’d already feel like it was theirs.

This is what’s missing in Puerto Rico right now, he believes. The worst has passed. Electricity is slowly returning. But what about the next Maria? All of this entrepreneurial energy -- the resurgent locals and the innovators coming with their cutting-edge resiliency technologies -- needs a central place to organize around disaster preparedness and recovery. The way Levin envisions it, this could become an open-air market: a hybrid pop-up space where military veterans teach preparedness skills to patrons amid food trucks, live entertainment and off-grid-technology exhibits. He’d been involved in a project like that in Miami -- minus the disaster element, of course -- and thinks it can work here, too.

Recently, Levin signed a one-year lease on an apartment in San Juan. He’s racked up a hefty credit card bill during his time here, but he’s determined to bring his new concept to life and recoup his costs in the process. “Puerto Rico is a phenomenal place to demonstrate this concept of community self-sufficiency,” he says. And if it’s successful, he wants to replicate the idea back in the continental U.S. -- and prepare us all for whatever is to come.

Gateway to Myanmar’s Past, and Its Future

NEW YORK TIMES | As Myanmar opens to the outside world — and an influx of tourists — after decades of totalitarian rule, its monuments attract scholars long put off by the country’s politics.

FIRST PUBLISHED IN THE NEW YORK TIMES, JULY 9, 2012

BAGAN, Myanmar — Fires, floods, treasure seekers and ficus trees have by turns withered this ancient royal capital, but in many ways it still looks as it might have eight centuries ago.

More than 2,200 tiered brick temples and shrines sprawl across an arid 26-square-mile plain on the eastern bank of the Irrawaddy River, remnants of a magnificent Buddhist city that reached its height in the 11th and 12th centuries.

These monuments, on a red-dirt plain thinly populated by monks and goat herders, are an unparalleled concentration of temple architecture, featuring sophisticated vaulting techniques not seen in other Asian civilizations and elaborate mural paintings whose counterparts have not survived well in India.

“It’s as if all the Gothic cathedrals were clustered in one spot,” said Donald Stadtner, author of “Ancient Pagan” and “Sacred Sites of Burma.”

As Myanmar opens to the outside world — and an influx of tourists — after decades of totalitarian rule, Bagan is far from the only site that is now of interest to scholars, many of whom were long put off by the country’s politics.

The Tibeto-Burman peoples from southwestern China who settled the upper Irrawaddy as early as the first century B.C. left behind large cities enclosed by brick walls and moats, and evidence of ingenious irrigation networks.

At Beikthano-Myo, one of the earliest of these settlements, archaeologists have found monasteries and shrines, or stupas, resembling those erected by Buddhists in eastern India, along with ornate burial urns and silver coins bearing auspicious symbols — marking the site as a staging point from which Buddhism spread across Southeast Asia.

Well before the political opening, Myanmar’s military rulers sought to restore historical monuments and establish local museums. In the late 1970s and ’80s, the authorities undertook a major rebuilding of Bagan, which an earthquake had devastated in 1975.

The restoration, supported by individual Burmese patrons eager to earn religious merit and by the United Nations Development Program, relied mainly on a close circle of domestic experts and has been sharply criticized by some outside scholars.

Critics took issue with the use of inauthentic building materials, like cement in place of stucco, and contend that certain architectural features — in particular the decorative finials that top religious monuments — were reconstructed according to imagination rather than science. A few prominent temples contain incongruous elements like disco lights flashing around the heads of Buddha statues.

“It’s been an unmitigated disaster,” Dr. Stadtner said of the restoration. “It’s as if every archaeological principle has been turned upside down in the past. I think there would be universal agreement that the damage to the monuments has been done, and is irreversible.”

Michael Aung-Thwin, a professor of Asian studies at the University of Hawaii and a longtime Myanmar scholar, dismisses such criticism as overstated, calling it “propaganda issued by the dissidents.”

“They made tremendous progress given the resources they had,” Dr. Aung-Thwin said.

U Win Sein, who was Myanmar’s culture minister during the 1990s, has defended the government’s renovations, which strived to reconcile antique preservation with Buddhist concepts of donation and refurbishment.

“These are living religious monuments highly venerated and worshiped by Myanmar people,” he wrote in a state-run newspaper. “It is our national duty to preserve, strengthen and restore all the cultural heritage monuments of Bagan to last and exist forever.”

Elizabeth Howard Moore, an archaeologist and art historian at the University of London, says she expects that Bagan will eventually be designated a World Heritage site, a change that will attract renewed interest from foreign scholars.

Many research questions at Bagan remain, including the nature of Buddhist life in the city and the relationship between the kingdom and its foreign neighbors. (Several of Bagan’s murals appear to have been painted by Bengali artists.)

Already, the new political climate has invited more foreign technical experts to bring the country up to international standards, and the Ministry of Culture is actively welcoming proposals by outside scholars.

“This was not happening 10 years ago,” Dr. Moore said. “The lifting of sanctions has not only brought renewed cultural awareness at a national level, but increased funding for business has started to encourage more and varied support for cultural and educational programs.”

Why Men Always Tell You to See Movies

NEW YORK TIMES | Why you never hear women doing voiceovers for movie trailers.

FIRST PUBLISHED IN THE NEW YORK TIMES, JANUARY 29, 2012

WHAT gender is the voice of God?

The question has been pondered by mystics through the ages, but in the sanctuary of cinema the voice of a sonorous, authoritative, fear-inspiring yet sometimes relatable presence is, invariably, that of a man. Consider the trailer and the omniscient, disembodied voice that introduces moviegoers to a fictional world.

“Most movie trailers are loud and strong, and film studios want that male impact, vocally and thematically,” said Jeff Danis, an agent who represents voice-over artists. “Even if it’s a romantic comedy or nonaction movie, they still want that certain power and drama that men’s voices tend to convey on a grander scale.”

Even now movie trailers and promos largely hew to a template created 40 years ago by Don LaFontaine, Hollywood’s most prolific voice-over artist. Possessor of a resonant baritone that could cut through tight sequences of music and sound bites — and the coiner of familiar (and parodied) phrases like “In a world ...” and “One man, one destiny” — LaFontaine, who died in 2008, voiced more than 5,000 trailers, thousand upon thousand of commercials and television promos.

Photo

Melissa Disney did the voice-over for the trailer for “Gone in 60 Seconds,” starring Angelina Jolie and Nicolas Cage. CreditTouchstone Pictures

In the past few years, as audiences have grown more sophisticated, the independent production companies that make trailers for Hollywood studios have begun moving away from voice-overs, favoring graphic devices like title cards to serve as narration. “As much as possible people are trying to let the movie speak for itself, without being as heavy handed as the ‘voice of God’ narrator feels,” said John Long of Buddha Jones Trailers, which was responsible for campaigns for “Kung Fu Panda 2” and “Inglourious Basterds,” among others.

Still, plenty of voice-over jobs remain, especially in television, though women are seldom cast. “There are some very talented, very gifted women in this business that can satisfy any request for a narrator, but the opportunities aren’t given to them,” said Mike Soliday, a talent agent who represents prominent male voice artists like Scott Rummell and Tony Rodgers.

As Mr. Danis put it, “Trailers are really the last frontier for women.”

Mr. Long noted that his company had worked on dozens of campaigns a year, “and as much as everyone talks about wanting to be innovative and do unexpected things, the idea of a female voice doesn’t come up that often,” he said. “It’s really not part of the formula. Maybe that’s our own shortsightedness.”

Asked to name a theatrical campaign that featured a female voice, trailer makers interviewed for this article could easily recall just one: “Gone in 60 Seconds,” the 2000 action thriller that starred Nicolas Cage and Angelina Jolie. “It was filled with really sexy and fast and fantastic-looking cars, and shot with a ton of energy,” recalled Skip Chaisson of Skip Films, who produced the trailer. “What else did it need? I thought it would be cool if we had a really sexy female voice. In a way we were doing a car commercial, so why not go as far with it as we can?”

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

Advertisement

Continue reading the main story

Melissa Disney, who did the voice-over for “Gone in 60 Seconds” and works frequently on television promos, commercials and animated series, argued that “men are very attracted to women’s voices, especially when they are sexy and sultry.” She continued: “Women have such a large range. We have so much more to pull from than your typical male action voice.”

One challenge women face is the perception in the industry that it’s difficult for their voices to be heard over a trailer’s cacophony, an attitude some voice-over artists dispute. “To say that a woman’s voice won’t cut through a trailer just isn’t true,” said Joan Baker, the author of “Secrets of Voice-Over Success” and a friend of LaFontaine’s. “What women’s voices have is emotionality and color and a certain kind of rhythm. Don would even say, ‘My voice isn’t right for everything.’ He felt it was ridiculous that women were not used in movie trailers. But no one wants to change what isn’t broken.”

Do moviegoers want to hear female voices? Research indicates that our brains are wired to prefer theirs to male ones; that’s the reason robotic voices, like those in GPS devices, tend to be female. (This probably has an evolutionary explanation: fetuses in the womb, identifying with their caretaker, can distinguish their mother’s voice from others, a study published in the journal Psychological Science found.) When it comes to credibility, however, research into the perceived believability of a voice — an important quality for the omniscient narrator of a trailer, as well as the spokesman or -woman for any product, which is the function a trailer serves — tells a different story.

“On average both males and females trust male voices more,” said Clifford Nass, a professor of communications at Stanford, noting some gender disparity exists in that women don’t distrust female voices as much as men distrust them. In one study conducted at Stanford two versions of the same video of a woman were presented to subjects: one had the low frequencies of the woman’s voice increased and the high frequencies reduced, the other vice versa. Consistently subjects perceived the deep voice to be smarter, more authoritative and more trustworthy.

Science aside, the conventional wisdom in the movie industry has it that audiences respond more favorably to trailers with male voice-overs. “People don’t buy that product from women, and I don’t know why,” said Seth Gaven of AV Squad, which produced the trailers and television campaigns for “The King’s Speech” and “Captain America.” “Female voice-overs don’t have the same credibility. Sometimes I’ll even consider a few guys with similar voices, and one might be a little more resonant and commanding, even in a subtle way. He usually gets the job.”

In television many cable channels regularly aim programming at women, and there has been more latitude in the use of female voices. “We’re all trying to make shows that cut through the clutter and stick out,” said Tim Nolan, senior vice president for marketing at Lifetime Networks. “But for me it’s less about being authoritative and more about being relatable. It’s a big turnoff for TV consumers if they think they’re being sold. Whether the show’s about fashion or drama or reality, it’s about which voice is telling those stories better.”

In testing “One Born Every Minute,” a Lifetime series set in an Ohio maternity ward, the channel found that audiences responded most favorably to a voice-over by Jamie Lee Curtis, even before they recognized her, Mr. Nolan recalled, adding: “One women said that the voice understood who she was.”

A Beautiful Mind

POPULAR SCIENCE | Can Ariel Garten's brain wave interface improve your outlook on life?

FIRST PUBLISHED IN POPULAR SCIENCE, JULY 2014

IN COLLEGE, ARIEL GARTEN started a clothing line that took its inspiration from neuroscience. She hooked people up to an electroencephalograph (EEG) to record their brain waves, then emblazoned T-shirts with the spiky patterns reflecting their mental activity. She also sewed skirts with 37 pockets, a reference to the number of different brain faculties described in the Victorian pseudoscience of phrenology, and filled them with bric-a-brac to represent the subconscious. At age 34, Garten is still making geek-chic designs—only now her creations can actually read people’s minds.

Garten is shoeless as she leads me through the Toronto headquarters of InteraXon, the start-up she co-founded in 2007. Her long brown hair nearly brushes her elbows as she pads along the wood flooring in brightly patterned socks. A whiteboard scribbled with nerdy wordplay and equations spans the length of one wall; neon Post-its are applied liberally elsewhere. Garten pushes open the door to a conference room called the Cerebroom and takes a seat at the table.

“I was always exploring relationships between art and science,” she says. During her stint as a fashion designer, Garten was double-majoring in psychology and biology at the University of Toronto, where she also began working with professor Steve Mann. A pioneer of wearable computers, Mann created digital eyewear to augment vision in the early 1980s. (“He basically developed Glass before Google,” Garten says.) Mann had also engineered a primitive brain-computer interface at MIT in the 1990s. Garten and some classmates decided to resurrect it to explore thought-controlled computing.

As a pilot project, the team produced a series of concerts at which audience members wore a version of the device. By manipulating their brain states, the spectators could influence the pitch and volume of synthesized instruments on stage. “We kept getting deeper and deeper into brain-wave technologies and what we could do with them,” Garten says. As they grew more ambitious—at points inventing a thought-controlled beer tap and levitating chair—the team formed InteraXon. For the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, they created an installation in which visitors could use a headset to control light displays on landmarks across the country, including Toronto’s CN Tower, Ottawa’s parliament buildings, and Niagara Falls, in real time.

“After the Olympics, we began looking at more complex applications,” Garten says. “And we realized we had a system that allowed you to form a relationship with technology.” InteraXon then set to work developing, in essence, a Fitbit for the brain—a wearable biofeedback device that measures neural activity, much like an activity tracker records steps and calories burned. “I think we’re all very curious about our own minds,” says Garten, “but we just may not have the tools to channel that.”

Garten passes me a sleek white headband called the Muse, the company’s first commercial product. The human brain contains billions of neurons that communicate via electrical impulses, and aggregate into waves of different amplitudes: Alpha, for instance, dominate when we’re relaxed or focused; beta kick in we problem-solve. The Muse transforms this brain activity into information that can be tracked wirelessly on a tablet or smartphone.

Muse is intended for daily use with an app called Calm, which features a three-minute exercise designed to help people manage stress. Through headphones, users can hear their brain waves represented as the sound of wind. Calm states beget gentle winds; distracted or agitated states elicit a roiling tempest.

Psychologists at Harvard University have shown that people spend 47 percent of their waking hours thinking about something other than whatever it is they’re trying to focus on. Neuroscientists call this tendency toward mental drift the “default mode network.” With neurofeedback, Garten believes people can build their cognitive strength. “If you’re having a crappy day, it can help you gain control of your mind,” she says. “Like, ‘I’m not calm now, but I know what to do to get there.’ ”

The Calm app follows in the tradition of the Buddhist principle of awareness, and the instructions it issues are similar to the Japanese Zen breath-counting meditation known as susokukan. Mindfulness, as such practices are popularly known, has been a growing focus of Western empirical research. The National Institutes of Health, for example, has funded dozens of studies that test mindfulness techniques.

Because InteraXon emphasized comfort when designing Muse, the device could be a valuable tool for scientists conducting such research. Norm Farb, a doctoral candidate in experimental psychology at the University of Toronto, is developing a six-week pilot study to measure the extent to which Muse can help control stress. “A lot of my research has looked at meditation and yoga, and there’s evidence that these can work for people with a mood problem,” Farb says. “So can Muse be training wheels for that?” With McMaster University in Ontario, InteraXon is examining how Muse can improve cognitive function, and an education lab at New York University is measuring the effect of Muse on learning.

There’s an obvious irony to the notion of computer-aided meditation. Many seek practices like mindfulness as an antidote to the distractions of today’s technology. We unplug to find calm. Garten appreciates this but says that sometimes people need a more accessible tool to achieve focus. “There are potential places that technology can take us that we can’t reach on our own,” she says.

Using InteraXon’s software, anyone can design compatible apps. Garten envisions a broad array of possibilities, including apps that treat children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and help athletes prepare for games. Eventually companies might get alerts when the brain waves of workers in high-stress jobs, such as air-traffic control, signal fatigue.

We leave the Cerebroom and walk past engineers conferring around workspaces cluttered with cables and prototypes. In the center of InteraXon’s office, a sitting area contains two egg-shaped chairs with speakers at ear level. Garten settles into one and gestures for me to take the other. “Imagine coming home and Muse senses you’ve had a stressful day,” she says, “and so the lighting adjusts and your home stereo starts playing your favorite relaxing music.” Garten sinks back into the chair with a slight, serene smile and closes her eyes.

Bliss and Sociability Where the Earth Draws a Bath

NEW YORK TIMES | Hot springs provide spiritual renewal and priceless views.

FIRST PUBLISHED IN THE NEW YORK TIMES, MARCH 19, 2009

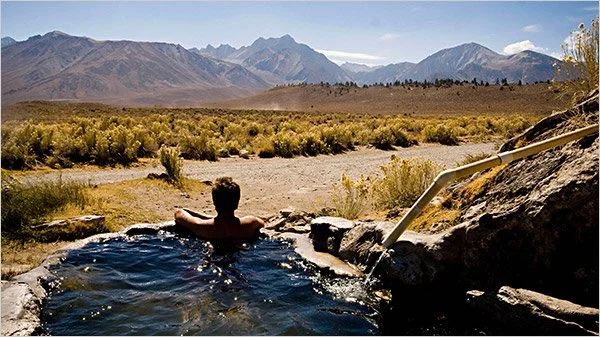

I WAS conceived into water. This doesn’t occur to me as a conscious thought so much as a body memory while I lie incubating, and shriveling, in a hole of thermal spring water on a high desert plain in eastern California.

But the experience sure seems womblike. Before me, the Sierra Nevada’s jagged crest looms naked and raw, as I no doubt appear in the tub. A breeze blows across yellow-tipped rabbitbrush, cooling my exposed shoulders. There are no other human beings around — none to warn about the dangers of overexposure, none to take my money — so into the soothing water I freely sink, my limbs spread open to a cloudless sky.

Not all hot springs evoke embryonic bliss. Others can be social affairs, resembling a Vegas hotel pool with more sulfur and body hair. Near my home in the San Francisco Bay Area, on occasion, the Pacific tide is low enough to expose a thermal spring trickling into a rocky tub on shore. Experiencing this ephemeral event requires descending a steep, unmarked path from Highway 1, usually at dawn.

The gaggle of bathers that converges there reminds me of those red-faced macaques I’ve seen pictured soaking in snowbound thermal pools in the Japanese Alps — only grooming, as Northern California’s higher primates do, with foot and shoulder massages. If this were New York, the tub might comfortably accommodate 6 strangers, but here, it packs at least 16. Comfort is culturally relative.

I love hot springs like these — undeveloped, natural and free. Nature’s spaamenities are largely immaterial: solitude and human connections, spiritual renewal and priceless views — even adventure. Cheap luxury is undeniably a draw, and when I first dip into a therapeutic spring I usually get giddy, like someone who has found himself and his backpack richly upgraded from a single room into a suite. But the sybaritic appeal goes deeper. The occasionally cramped tubs, the inconvenience of getting to them — these are appropriate compromises for what a pool of thermal water lying bare on the earth’s surface affords: immersion into something ancient and primordial.

The American West is pockmarked with hot springs. Heated by deep magma chambers, much of the water emerges scalding or inaccessible on private property. But in rare instances it arrives at a delightful temperature on scenic public lands where it is available to all comers as a quasi tax return.

My initiation was as a new college graduate on a westward migration. The hot spring, in Oregon, was as much an introduction to West Coast culture as a means to soothe driving-muscle aches. Nude public bathing was foreign to me at the time, but I soon understood that wearing a bathing suit in this kind of spring was like using a fork in an Ethiopian restaurant: culturally awkward, somewhat antisocial and generally antithetical to the underlying idea. The forced intimacy between undressed strangers actually encourages friendly and inspired chatter, as it might between travelers meeting at a remote oasis.

Since I settled in California, books like “Hot Springs and Hot Pools of the Southwest” by Marjorie Gersh-Young and printouts from soak.net have become my faithful road trip companions. (The location of some undeveloped tubs is closely guarded by locals, revealed only after cultural profiling; wearing a fanny pack would probably not help.)

While driving across the desolate Highway 50 through central Nevada, on a trip from San Francisco to Colorado, I was directed down a washboard side road seemingly toward the middle of nowhere. Wild burros grazed in sagebrush. After a cattle guard and a turn, three steaming tubs were suddenly revealed, perched on the edge of the wide, deserted valley with a stunning panorama of the Toiyabe Range. I recall thinking, as a bargain hunter might: Why would anyone ever pay full retail for this? Someone — hot springing has an industrious volunteer subculture — had laid smooth stone seats inside the tubs and wood platforms on the rim. As I settled into the sublimity, my nose picked up a faint whiff of a deer carcass. Or maybe it was a burro. Either way, aromatherapy it was not, but I was hooked.

Every hot spring has its own authenticity, and over time I have developed an appreciation for their diversity of scenes and settings. A spring on the east bank of the Rio Grande, outside Taos, N.M., invites dips in the warm tubs after lazy floats downriver, a cycle I once repeated for hours, until my raisin hands looked like something I should be concerned about.

Just reaching an isolated spring deep in the mountains of Big Sur requires a 10-mile hike through coastal redwoods and chaparral. I visited with my girlfriend; romantic touches — candles left by previous soakers on the mossy ledges of the rock-lined tubs, the babble of an adjacent river — inspired a communion with the surrounding forest.

When possible, I figure hot springs into my travels abroad. Much like, say, birding, visiting hot springs is a conceit for seeing a country off the beaten track, and their universality allows me to transcend the foreignness of a place. Thermal water is comfortable and familiar, even while the geography or culture is not.

The Blue Lagoon in Iceland may be that geothermal hot spot’s most iconic pool of therapeutic water, but my most memorable Icelandic soak was under the dusky midnight sky on rural land owned by a provincial church, which doesn’t make branded anti-aging creams. The only inhabitant around, a half-mile from the unmarked spring, was the pastor himself, who actually lived with a flock of sheep. After my soak, I visited him, and as we spoke he politely excused himself to assist a ewe in labor, which he did successfully, wearing a tweed sport coat.

Paradoxically, it was at a hot spring in one of the most remote and inhospitable parts of the planet where I was made to feel most deeply at home. The Salar de Chalviri, in southwest Bolivia, is a forbidding volcanic region at about 14,000 feet in elevation, where spring water of pleasurable temperature collects in small pools on the rocky, mineral-stained soil. There is a God’s Country quality to the place. When I passed through there one morning on a Jeep tour, the tubs afforded a sanctuary, a geothermal mikva, amid the denuded landscape. The sun’s slanted light mixed with steam rising off the water to produce an ethereal glow, leaving me to bathe soulfully in the gift of creation.

How the Dark Knight Became Dark Again

THE ATLANTIC | Batman started serious, went campy in the '60s, and was steered by a superfan back to the grimness of Tim Burton's 1989 movie and of Christopher Nolan's present-day trilogy.

FIRST PUBLISHED IN THE ATLANTIC, JULY 17, 2012

The Batman who shows up in Friday's The Dark Knight Rises actually is something like your grandfather's Batman. Uttering a barely intelligible growl, facing off against villains that recall real-life terrorists, and confronted again and again by his own mortality, the Bruce Wayne imagined by director Christopher Nolan reflects the grim avenger that debuted in 1939, so po-faced that in 2008's The Dark Knight the Joker took to taunting him about it: "Why... so...serious?"

Batman has been so successfully remade in recent years that we scarcely remember how, for a generation, the Dark Knight lived in the public imagination as a pot-bellied caped crusader with a goofy sidekick. ABC's live-action BatmanTV series, which ran from 1966 to 1968, was deliberately campy ("To the Batpole!") and created a long-enduring association between the superhero and the cartoonish onomopeias "Pow!" "Zap!" and "Wham!"

The story of how the farcical Batman of the '60s transformed into the solemn one of today mirrors the elevation of the comic book in general from belittled kiddie fare to the subject of academic inquiry and box-office-breaking, R-rated action movies. It's also a story of a 73-year-old franchise returning to its roots, reflecting its times, and helping build a multibillion dollar industry that churns out branded merchandise, video games, theme park attractions and annual conventions. And it's the story of one fan named Michael Uslan, who, as an 8th grader in the '60s, made a vow to save Batman.

USLAN GREW UP IN NEW JERSEY, the son of a stonemason and a bookkeeper, and escaped into comic books. He first discovered the Harvey Comics—Richie Rich, Casper, and Little Archie, by Archie Comics Group—and later Superman, which turned into an obsession. (He would write letters to the editors notifying them of "boo-boos" he spotted on the pages.) At age eight, Uslan graduated to the scarier Batman comics, where like many children, he found a hero to emulate. "I truly believed that if I studied real hard, and worked out real hard, and if my dad bought me a cool car, I could become this guy," Uslan, now 60, says. "That was when I said, 'I want to write Batman comics.'"

The ABC Batman series Uslan saw on TV didn't reflect the comic-book superhero he so loved. Producer William Dozier reportedly instructed Adam West, who played Batman, to deliver the caped crusader's silly lines "as though we were dropping a bomb on Hiroshima, with that kind of deadly seriousness." All of this pained Uslan, then a nerdy teenager. "The whole world was laughing at Batman and that just killed me," he says. "One night I vowed to erase from the collective consciousness those three little words: Pow! Zap! and Wham! I said, 'Somehow, someday, someway, I am going to show the world what the true Batman is like.'"

The true Batman, to Uslan, was the character originally co-created in 1939 by DC Comics' Bob Kane and Bill Finger, who imagined Batman as a shadowy creature that stalked criminals under darkness. Kane and Finger drew their inspiration from divine heroes throughout the ages, as Superman's creators has done before them, only they made Batman out to be more like Zorro and the Shadow, the dark mystery men of silent movies and pulp fiction. While the makers of Superman "played with the bright and impossible, Bob and Bill expanded that meme by adding the coin's other side, the dark and improbably possible," writes Travis Langley, a professor of psychology at Henderson State University. "Duality and obsession, his enemies' and his own, fill his stories." (Later, after Robin was written, Batman was softened to fall in line with Superman and the publisher's other more agreeable heroes.)

As an undergraduate, Uslan attended Indiana University, which at the time had an experimental curriculum department in the College of Arts & Sciences that allowed any student to pitch an idea for a non-traditional course that had never been taught before, and if the faculty approved, teach it. Naturally, Uslan created a course on comic books as modern day mythology ("the gods of Egypt, Greece and Rome still exist, although today they wear spandex and capes"), and presented his case before a committee in an Amazing Spider-Man t-shirt—"for impact," he later said. One dean, Uslan says, scoffed at the idea of comics as contemporary folklore. Uslan asked if he was familiar with the story of Moses. The dean said he was, so Uslan asked to indulge him by recounting the tale. Then, Uslan asked him to recall the origin of Superman, which begins with a scientist and his wife placing their infant son in a little rocket ship. "Suddenly, the dean stopped talking. He stared at me for what I was sure was an eternity," Uslan writes in his memoir, The Boy Who Loved Batman. "And then he said, 'Mr. Uslan, your course is accredited.'"

Uslan says he took the news to United Press International, the wire service based in Indianapolis. Pretending to be an offended citizen, he asked to speak with the education beat reporter. "I hear there's a course on comic books being taught at Indiana University," he said. "This is outrageous! Are you telling me as a taxpayer that my money is going to teach our kids comic books?! It must be some Communist plot to subvert the youth of America!"

Uslan was playing to a prevailing cultural sentiment that held comic books responsible for a range of social ills. Fredric Wertham, a German-born American psychiatrist who made his name as a consulting psychiatrist for the New York court system and was a champion for civil rights (he provided information that helped the Supreme Court end school desegregation), was its most vocal exponent. In his 1954 book Seduction of the Innocent, Dr. Wertham argued that crime comics were behind a rise in juvenile delinquency—a view foreshadowing modern-day arguments about violent video games—and that comic books in general stilted kids reading, created young Communists, and caused asthma, since children were playing outside less. Boys who read The Adventures of Batman and Robin could become gay, and girls who read Wonder Woman could become lesbian. Testifying before the United States Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, which took up his concerns, Wertham is said to have declared that "Hitler was a beginner compared to the comic-book industry."

The backlash that Wertham inflamed ultimately stoked comic-book burnings in some American communities, and led to the creation of the Comics Code Authority, a code of self-censorship that forbid suggestive postures, banned sympathetic criminals and the portrayal of drug use, and also demanded realistic drawings of women, exaggerated bosoms be damned. The code lasted up until just last year.

Uslan's feigned indignation paid off. UPI ran with the story of the world's first accredited university course on comic books, and the long-haired Uslan was soon taking interview requests from major television networks, newspapers, and magazines like Family Weekly and Playboy. Three weeks later, his phone rang: It was Stan Lee from Marvel Comics, the venerated co-creator of Spider-Man, X-Men, Fantastic Four, The Hulk, and the entire pantheon of Marvel superheroes. "This course you're teaching is great for the entire comic book industry," he told Uslan. "How can I be helpful?" Then, just two hours later, Uslan recalls, the vice president of DC Comics in New York—the publishers of Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman—also phoned. He wanted to offer Uslan a summer job.

One morning that summer, Uslan says, he was walking by the office of an editor of the series The Shadow, when he overheard the editor complaining about a script he needed finished by the next day. Uslan poked in his head and offered to pinch-hit, making up something about a great story idea he had. Overnight, Uslan became a comic-book writer. A few weeks later, the editor of Batman, Julie Schwartz, passed him in the hallway and complimented his script on The Shadow("it didn't stink"). Would he like to take a crack at writing Batman?

FOR USLAN, fulfilling his childhood dream to write Batman comics called for a new goal, and he set his sights on making the "dark and serious" movie that would redeem the Kane-Finger character. He says that Sol Harrison, the vice president of DC Comics at the time, assured him this was foolhardy. Ever since the ABC show had left the air, he told Uslan, Batman was "as dead as a dodo." What's more, Uslan knew nothing about making movies. He sold 20,000 of comic books from his own collection to raise tuition for an entertainment law degree and fresh out of school took a position as an attorney for United Artists, handling legal and business affairs for films like Apocalypse Now, Raging Bull, and the early Rocky movies.

Together with Ben Melniker, a former MGM exec who had put together the deals for Ben-Hur, Dr. Zhivago, and 2001: A Space Odyssey, the two fielded money from individual investors, and on October 3rd, 1979, for an undisclosed sum, optioned the film rights to "Batman" from DC Comics, forming Batfilm Productions.