Can a Better Vibrator Inspire an Age of Great American Sex?

THE ATLANTIC | Sex toys have transformed into sophisticated and well-designed gadgets that take their inspiration from Apple not Hustler. But one company has a bigger hope: that a better machine could mean better sex for a repressed nation.

FIRST PUBLISHED IN THE ATLANTIC, MAY 14, 2012 (Republished in “Best Sex Writing 2013”)

THE OFFICES OF JIMMYJANE are above a boarded-up dive bar in San Francisco's Mission district. There used to be a sign on a now-unmarked side door, until employees grew weary of men showing up in a panic on Valentine's Day thinking they could buy last-minute gifts there. (They can't.) The only legacy that remains of the space's original occupant, an underground lesbian club, is a large fireplace set into the back wall. Porcelain massage candles and ceramic stones, neatly displayed on sleek white shelves alongside the brightly colored vibrators that the company designs, give the space the serene air of a day spa.

Ethan Imboden, the company's founder, is 40 and holds an electrical engineering degree from Johns Hopkins and a master's in industrial design from Pratt Institute. He has a thin face and blue eyes, and wears a pair of small hoop earrings beneath brown hair that is often tousled in some fashion. The first time I visited, one April morning, Imboden had on a V-neck sweater, designer jeans and Converse sneakers with the tongues splayed out -- an aesthetic leaning that masks a highly programmatic interior. "I think if you asked my mother she'd probably say I lined up my teddy bears at right angles," he told me.

Imboden was seated next to a white conference table, reviewing a marketing graphic that Jimmyjane was preparing to email customers before the summer season. Projected onto a wall was an image that promoted three of Jimmyjane's vibrators, superimposed over postcards of iconic destinations -- Paris, the Taj Mahal, a Mexican surf beach -- with the title: "Meet Jimmyjane's Mile High Club: The perfect traveling companions for your summer adventures." The postcard for the Form 2, a vibrator Imboden created with the industrial designer Yves Behar, was pictured alongside the Eiffel Tower with the note: " Bonjour! Thanks to my handy button lock I breezed through my flight without making noise or causing an international incident. See you soon, FORM 2."

Jimmyjane's conceit is to presuppose a world in which there is no hesitation around sex toys. Placing its products on familiar cultural ground has a normalizing effect, Imboden believes, and comparing a vibrator to a lifestyle accessory someone might pack into their carry-on luggage next to an iPad shifts people's perceptions about where these objects fit into their lives. Jimmyjane products have been sold in places like C.O. Bigelow, the New York apothecary, Sephora, W Hotels, and even Drugstore.com. Insinuating beautifully designed and thoughtfully engineered sex toys into the mainstream consumer landscape could push Americans into more comfortable territory around sex in general. Jimmyjane hopes to achieve this without treading too firmly on mainstream sensibilities. "Not everyone sits in a conference room and talks about vibrators, dildos, anal sex, clitorises -- and we do," Imboden explained. "It's important for us to remain a part of the mainstream culture and sensitive to how normal people discuss or don't discuss these subjects."

Ten years ago, walking into the annual sex toy industry show for the first time, Imboden was startled by the objects he encountered. He had developed DNA sequencers for government scientists at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and more recently he had left a job designing consumer products -- cell phones and electric toothbrushes -- for companies like Motorola and Colgate, work he found dispiriting. "It was imminently clear to me that I was creating a huge amount of landfill," Imboden told me. "I wanted no part of it." He struck out on his own, and found himself approached by a potential client about designing a sex product.

The floor of the Adult Novelty Manufacturers Expo, held that year on the windowless ground level of the Sheraton in Universal City, California, flaunted fated landfill of a different sort: a gaudy display of "severed anatomy, goofy animals, and penis-pump flashing-lights kind of stuff," Imboden recalled. These tawdry novelties dominate the $1.3 billion-a-year American sex toy market. They are the output of a small but cliquish old boys' network of companies you've probably never heard of, even if you have given business to them. One of these, Doc Johnson, was named as a mocking tribute to President Lyndon B. Johnson, whose justice department in the 1960s tried in vain to prosecute the late pornographer Reuben Sturman, the industry's notorious founding father. Sturman invented the peep show booth, and built a formidable empire of adult bookstores that for decades constituted the shadowy domain where such products were sold, usually to men.

Imboden was inspired. "As soon as I saw past the fact that in front of me happened to be two penises fused together at the base, I realized that I was looking at the only category of consumer product that had yet to be touched by design," Imboden said. "It's as if the only food that had been available was in the candy aisle, like Dum Dums and Twizzlers, where it's really just about a marketing concept and a quick rush and very little emphasis on nourishment and real enjoyment. The category had been isolated by the taboo that surrounded it. I figured, I can transcend that."

At dinner parties in San Francisco, where he lives, Imboden found that mentioning sex toys unleashed conversations that appeared to have been only awaiting permission. "Suddenly I was at the nexus of everybody's thoughts and aspirations of sexuality," he said. "Suddenly it was OK for anyone to talk to me about it." It occurred to Imboden that the people who buy sex toys are not some other group of people. They are among the half of all Americans who, according to a recent Indiana University study, report having used a vibrator. They are people, like those waiting outside Apple stores for the newest iPhone model, who typically surround themselves with brands that reinforce a self-concept. They spend money on quality products, and care about the safety of those products. Yet, for the very products they use most intimately--arguably the ones whose quality and safety people should care most about--they were buying gimmicky items of questionable integrity. It's just that people had never come to expect or demand anything different--silenced by society's "shame tax on sexuality," as one sex toy retailer put it to me. And few alternatives existed.

Jean-Michel Valette, the chairman of Peet's Coffee, who would later join Jimmyjane's Board of Directors, told me: "I had thought the opportunities for really transforming significant consumer categories had all been done. Starbucks had done it in coffee. Select Comfort had done it in beds. Boston Beers" -- the makers of Samuel Adams -- "had done it in beer. And here was one that was right under everyone's nose."

Jimmyjane's success has inspired a growing class of design-conscious companies--including Minna, Nomi Tang and Je Joue--that are beginning to clean up an unscrupulous industry long cloaked by American discomfort around sex. LELO, a Swedish brand founded by industrial designers, creates up-market products with names--Gigi, Ina, Nea-- that sound like feminized IKEA furniture. (Try Gigi on the SVELVIK bed!) OhMiBod, a line of vibrators created by a woman who once worked in Apple's product marketing department, synchronize rhythmically with iPods, iPads, iPhones and other smartphones.

I asked Imboden what qualified him to design a vibrator, a device primarily intended for female pleasure. Imboden said he considers himself "decidedly heterosexual," but also "universally perceptive," and he suspects that the formative childhood years he spent living with his mother and older sister, after his father died of cancer when he was two, may have nurtured within him a certain empathy for the opposite sex. (His father had also been an engineer, also worked at Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, and ended up starting a dressmaking company called Foxy Lady.) "Ethan has an intellectual curiosity and an emotional maturity that doesn't stop him from exploring something that a man 'shouldn't,'" said Lisa Berman, Jimmyjane's C.E.O., who came from The Limited and Guess and is among the company's all- female executive team. "He is a real purist in the way he thinks, not just about engineering and design but the emotional connection that these products might assist in a relationship. He can do that better than anyone that I've met."

Imboden enlisted his mother and sister to help him start the company. These made for some strange moments, as in the time when his mom complimented him on a well-written description of how a vibrator could be inserted safely for anal use, calling out from across the room, "Ethan, you handled the anus beautifully." His friend Brian and other close friends invested initial seed money. Professional investors were intrigued but hesitant; here was a first-time entrepreneur, making a consumer product that was not, strictly speaking, technology (being the Bay Area this mattered)--and it was about sex. "They were scared of it," Imboden said. (Banks still refuse their business, citing vague "morality clauses.") Tim Draper, a prominent Silicon Valley venture capitalist known for backing ventures like Skype and Hotmail, thought differently. "He had a unique way of looking at the world, and a great sense for product design," Draper wrote to me in an e-mail. "He understood branding."

Little Gold, Jimmyjane's first vibrator, is a slender thing that could be mistaken for a cigar case. Imboden developed and patented a replaceable motor that slides inside the 24-carat gold-plated shell, which he engineered to vibrate in near silence. It is a portable, durable, and waterproof sex toy designed never to become landfill. For Imboden, it was merely a proof of concept. "It's an immediate of disruption of the associations that we have with sexual products," he said.

The trendy London-based apothecary, Space.NK, bought the concept, and displayed Jimmyjane right next to Marc Jacobs' new fragrances. Soon after, Selfridges, the high-end British department store, carried the company's products. For Imboden, debuting in European retailers was a deliberate end-run around American social taboos, and also made a sidestep of the sex toy industry entirely. It was a statement that products like vibrators did not have to be relegated to their own store or a discreet Web site. Premiering in lofty precincts before trickling down to the mainstream borrowed from a fashion playbook: Little Gold could be thought of as Jimmyjane's couture offering, its runway showpiece. A more accessible aluminum version, Little Chroma, now sells for $125 at Drugstore.com.

Early on, Imboden would also hang around celebrity gatherings, putting vibrators in the hands of influencers. After the Grammy Awards one year, he found himself walking across an intersection in front of a white low rider. Inside, two heads bobbed to music; "Snoop de Ville" ran across the side of the car. As Imboden jogged over to the front window, he reached inside his shoulder bag for a vibrator, and "it dawns on me that this is a perfect recipe for getting shot," he recalls. Snoop Dogg was behind the wheel, talking on a cell phone; a chandelier swayed gently above him. Imboden handed him a Little Something. "This dude just gave me a 24k gold vibrator," Snoop relayed into the phone. Then he turned to Imboden. "Thank you, my nigga. I'm gonna put this to work right now."

In January 2005, the Little Gold made it into the Golden Globe Awards gift suite, the freebie swag lounge that, in those days, A-list celebrities actually visited. "To have a non-fashion item like that at one of these showcases was really unusual and groundbreaking," Rose Apodaca, the West Coast bureau chief of Women's Wear Daily at the time, told me. "It was the hot item everyone was trying to get their hands on." Teri Hatcher and Jennifer Garner, by picking one up, became among the brand's first celebrity endorsers. Apodaca wrote about it in WWD's awards season special. "Suddenly there's this tool for sex being featured in the bible of the fashion industry." After Kate Moss was spotted purchasing a Little Gold from a Greenwich Village lingerie boutique -- a "buzz-worthy bauble," Page Six wrote -- Jimmyjane appeared in Vogue.

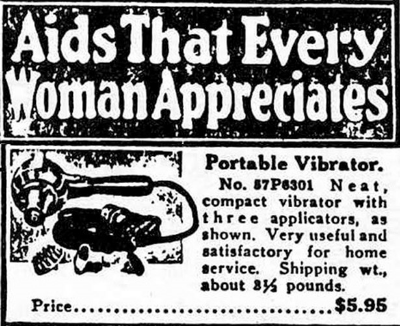

After the introduction of electric lights in 1876, home appliances were plugged in, one by one, beginning with the sewing machine and followed by the fan, the teakettle, the toaster and then, the vibrator. (The vacuum cleaner would come ten years later.) Ads for them appeared in Hearst's, Popular Mechanics, Modern Women and Women's Home Companion, among many others. A National Home Journal ad in 1908 for a $5 hand-powered vibrator, declared: "Gentle, soothing, invigorating and refreshing. Invented by a woman who knows a women's needs. All nature pulsates and vibrates with life." Another in American Magazine claimed that the vibrator "will chase away the years like magic...All the keen relish, the pleasures of youth, will throb within you...Your self-respect, even, will be increased a hundredfold." A Sears, Roebuck catalog in 1918 advertised a portable vibrator on a page (with fans and household mixers) of "Aids That Every Woman Appreciates."

Was this language camouflage for an orgasm? Were these vibrators also intended, with a wink, for masturbation? This has become the popular history of the device as written by Rachel Maines, a Cornell researcher, who argued in her 1999 book "The Technology of Orgasm" that electric vibrators replaced the hands of doctors who, from the time of Hippocrates to the 1920s, had been massaging women to orgasm as a treatment for hysteria.

Hysteria: The 17th century French physician Lazare Rivière's described it as "a sort of madness, arising from a vehement and unbridled desire of carnal embracement which desire disthrones the Rational Faculties so far, that the Patient utters wanton and lascivious Speeches." Today, this sounds a lot like normal functioning of female sexuality. But men long viewed it as a disorder. During antiquity physicians believed that hysteria was caused by the womb meandering around the body, wrecking havoc, yet by the 19th century the term had become "the wastepaper basket of medicine where one throws otherwise unemployed symptoms," as the French physiatrist Charles Lasègue put it. (The American Psychiatric Association finally dropped hysteria altogether from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in 1952, the same year it added homosexuality.)

Virgins, nuns, widows and women with impotent husbands were thought especially prone. Victorian physicians, especially in England and the United States, were wary of female arousal. They viewed it as a dangerous slope towards uncontrollable desires and ill health, and advised women against tea, coffee, masturbation, feather beds, wearing tight corsets, and reading French novels.

Maines argues that relieving women of this pent-up desire was a standard medical practice. She takes us back to the Greek physician Soranus, who in the first century A.D. discussed his treatment: "We...moisten these parts freely with sweet oil, keeping it up for some time," he wrote. Helen King, a historian and leading authority of Classical medicine at England's Open University, told me that a correct translation of this passage has him massaging the abdomen, the typical treatment for yet another female disorder--chronic flowing of female "seed"--for which rose oil was prescribed, along with cold baths and avoiding sexy pictures. Rather, King says, it is with the influential Roman physician Galen where we see the first explicit mention of genital massage to orgasm as a medical treatment. Galen discusses a woman rubbing "the customary remedies" on her genitals--sachets of Artemisia, marjoram and iris oil--and feeling the "pain and at the same time the pleasure" associated with intercourse.

But did doctors do the deed? Probably not in antiquity, King said--there was a taboo against such things even back then, and the task was likely assigned to midwives. References in the annals of medicine to genital massage are oblique, leaving a trove of circumstantial evidence, with some exceptions, like the British physician Nathaniel Highmore complaining in the 17th century that massaging the vulva was "not unlike that game of boys in which they try to rub their stomachs with one hand and pat their heads with the other." Maines believes that doctors considered this a tedious task, and not a sexual act, since sexual relations, especially in those pre-Clinton centuries, meant proper intercourse. However, if intercourse failed to relieve the symptoms of desire--only recently have we known that up to seventy percent of women cannot reach orgasm from intercourse alone--doctors prescribed hydrotherapy (the douche sprays in Saratoga Springs, NY were a popular destination for women whose husbands were at the racetrack) or an office visit.

In 1869 an American physician, George Taylor, patented a steam- powered contraption called the "Manipulator," in which a patient lay stomach-down on a padded table and received a pelvis massage from a vibrating sphere. The Chattanooga, a 125-pound apparatus that sold in 1904 for $200, was used on both sexes for various treatments including, the company's catalog described, "female troubles." All manner of inventions were marketed to doctors: musical vibrators, vibratory forks, vibrating wire coils called vibratiles, floor-standing models on rollers and portable devices shaped like hair dryers. They were powered by air pressure, water turbines, gas engines, and batteries. We don't really know how common the practice of massaging women with these devices actually was--Maines's book touched off a debate among sex historians, with some arguing that it was probably rare and considered quack medicine--but in any case, after the first electromechanical vibrator was patented in 1880, vibrators marketed for home use flourished. General Electric and Hamilton Beach both made handheld devices that looked like hair dryers, boxed with various attachments. (I recently found a 1902 Hamilton Beach vibrator listed on eBay for $25.99.) Women could now regain the "pleasures of youth" through their own devices.

For reasons that are not entirely clear, vibrator ads gradually disappeared from up-market magazines after the 1920s, and went underground. Fifty years later they would resurface -- Hitachi's Magic Wand Massager first appeared in the 1970s and remains one of the top- selling vibrators, even though the company will tell you it doesn't make vibrators -- and feminists in New York City began teaching women self-pleasure. By the 1990s, Bob Dole was talking about erectile dysfunction as the pitchman for Viagra, and the Starr Report described fellatio and a semen-stained dress, pushing the boundaries of acceptable mainstream media conversation.

And then, Miranda presented Charlotte with the Rabbit Pearl, a pink, phallus-shaped vibrator with rotating beads and animated bunny ears, on prime-time cable television.

Everyone in the sex toy business whom I spoke with credits "Sex and the City" with profoundly changing the way Americans now talk about sex toys. The Rabbit Pearl became an overnight sensation -- "Talk about product placement," the vibrator's manufacturer, Dan Martin of Vibratex, told me. With clean, well-lit stores like Good Vibrations and Babeland; the Tupperware-inspired, sex-toy house gatherings for women known as Pleasure Parties ("Where Every Day is Valentine's Day"); and the Internet -- which opened all kinds of new avenues for sexual adventure -- women now had safe and discreet places to buy it. The Rabbit Pearl is still the top-selling sex toy, although the original from Vibratex has been knocked off so many times that "the rabbit" has become generic.

In an episode during the fifth season of "Sex and the City," Samantha walks into a Sharper Image to return her vibrator.

"We don't sell vibrators," the clerk tells her.

"Yes you do, I bought this here six months ago," Samantha replies, holding up the device."That's not a vibrator," he says, "that's a neck massager."

Within Sharper Image, that neck massager became known jokingly as "the Sex and the City vibrator," but in 2007, Imboden approached the company with the Form 6. Literally the sixth in a series of vibrator sketches -- Imboden believes in minimalist names -- the Form 6 has a curved, organic shape that is suggestive without being representational. It is wrapped completely in soft, platinum silicone, making it completely water-resistant, and charges on a wall-powered base station through a narrow stainless steel band, a novel cordless recharging system that Imboden patented. For these features, the Form 6 earned an International Design Excellence Award, the first time a sex toy had earned such a distinction. It comes in hot pink, deep plum or slate-- non-primary, poppy colors that he believes convey sophistication. It is packaged in a hard plastic case inside a bright white box -- "literally and figuratively bringing these products out of the shadows," Imboden said. And it has a 3-year warranty (this may not seem remarkable, but is for a sex toy).

"It was certainly controversial internally," recalled Adam Ertel, Sharper Image's buyer at the time. Sharper Image decided to try the Form 6 in a few stores -- "a waterproof personal massager" is how they described it -- and, to everyone's surprise, the Form 6 soon became one of the retailer's best selling massage items. They quickly rolled it out nationwide. "It was clear to all of us that we were treading on new ground," said Ertel. "We realized that the people that bought the Form 6 for its intimate nature may be a large group of consumers that people aren't strategically selling to."

One afternoon in May, I joined Imboden at a meeting with Yves Behar to talk through ideas for the Form 4, their next vibrator. They met at Behar's downtown San Francisco design studio, fuseproject, around a conference table topped with some rudimentary prototypes that they would pick up and flex in different directions while discussing "torque" and "harmonics" and "programming sequences." On a counter along the back wall stood a desk lamp that Behar designed for Herman Miller. Behar is perhaps best known for creating the One Laptop Per Child computer and perhaps least known for designing both New York City's branded bike helmet and its official condom dispenser. The two had been friends for a while -- Behar was an early advisor to Jimmyjane -- before deciding, a couple years ago, to collaborate. "Isn't this that old fashioned Playboy mansion cliché, two guys coming up with products used for women?" Behar asked. "I don't know if it is because I have twenty-plus years experience of design or thirty years of sexual experiences. You put the two together and you can get to some really interesting places."

During the initial brainstorms, which included the women on their respective teams, some awkward workplace conversations, and plenty of giggling, Imboden and Behar identified three different functions that a vibrator should deliver. They decided to roll them out in a trio of devices -- a collection they've named "Pleasure to the People" -- all built upon a modular base structure that houses a common digital interface, wireless rechargeable battery and motor. They designed the Form 2, their first product, to be a "new interpretation" of the Rabbit Pearl. Its form is compact, resting ergonomically in the palm of the hand, with a novel shape that resembles a padded tuning fork or a portly, marshmallow Peep Easter bunny -- suggestive enough of the iconic Rabbit to appear familiar to people, but amorphous enough that they don't dwell too much on what it looks like. "It's not just a lumpy random shape," Imboden pointed out. "I think there's a real sense of purpose in the forms which communicate that this is not an arbitrary act or a whimsical random thing we've created."

Through their design, Imboden wants to convey the sense that these are carefully considered objects--that someone is looking out for our sexual well-being, even if we have been conditioned to have low expectations. "I jokingly say this is an area where you really don't want to disappoint your customers," Behar told me. "And I think this is an industry that has treated its customers really badly." The Form 2 takes a symmetrical, organic form but they avoid emulating anatomy, because while "the penis is very well designed to accomplish what it needs to accomplish, a vibrator doesn't actually need to do those same things," Imboden said. One function it was not designed to accomplish was to stimulate a woman's G spot, but even if it did, mimicking male genitalia treads on psychological territory that Imboden would rather avoid. "While on the one hand that has its own excitement, there becomes a third person," he said, noting that some men feel threatened by an object they perceive to be a substitution for themselves. "People aren't necessarily seeking to have a threesome. Our goal has really been for the focus to be on you and your sensations and the interaction with your partner and not really to pull attention to the product itself. That's an element of why we make the products as quiet as they are. It's also why we make them visually quiet." Representational objects, like taxidermy hanging in a lodge, take up psychic space; figurative forms leave fantasy open to one's own interpretation. "Staying away from body shapes," Imboden explained, "is a way of keeping open provocative possibility, as opposed to narrowing it down to a provocative prescription."

The Form 3, the second vibrator designed with Behar, has a vibrating, ultra-thin soft silicone skin that flexes into the curve of the palm. The Form 4, the two men discussed that afternoon, should "deliver an oomph." Imboden believed they could achieve this by setting two motors to vibrate at different frequencies. Behar pondered an internal structure that would allow the vibrator to bend in various directions, similar to the neck of his Hermann Miller lamp. "Plus it makes it looks exactly like Barbapapa, my childhood hero," he said, referring to the popular French cartoon creature that looks like a pear-shaped blob and can change shape. "For each of these projects we came up with some funny metaphors," he told me. "It keeps you true to the original concept."

From a study released in 2009 by Indiana University, the first academic, peer-reviewed study to look at vibrator use, we now know that 53 percent of women and nearly half of all men in the United States have used a vibrator. This makes it nearly as common an appliance in American households as the drip coffee maker or toaster oven, The New York Times reported, and about twice as prevalent among American adults as condoms, according to Church & Dwight, maker of Trojan condoms, which funded the Indiana University study. Jimmyjane's own sales reveal that as many men as women, as many 25-

year-olds as 50-year olds, and as many Virginians as Californians, per capita, are buying vibrators. At each phase of life, a sex toy might take on new meaning; perhaps, initially, as a way to explore one's own body, but later, within a long-term relationship, as a way to sustain excitement. Today sex therapists are hearing more discussion of what they call "desire discrepancies" -- one partner wanting sex more, or less, or in a different manner, than the other. "Our bread and butter used to be orgasm and erection problems," said Sandor Gardos, a sex therapist, adding that self-help sources and Viagra have arisen to address those issues. "There's more discussion now around the subtle and complex issues of relationship and sexuality."

Imboden sees Jimmyjane as playing into that discussion around sex and well-being, not only as a peddler of "marital aids" -- terminology still used by the handful of online sex-toy retailers catering to religious Christians -- but as a trusted provocateur. Guests looking for condoms at W Hotels will find Jimmyjane's Pocket Pleasure Set in their room's mini bar, a slim package containing condoms, a mini vibrator, a feather tickler, and the "love decoder"--a piece of paper folded like an Origami fortune teller that engages players in titillating acts through a game of chance. "Everybody wants to try these new boundaries but they need a catalyst to make this happen," Imboden told me. "We are granting them permission by transferring the responsibility to us."

One day, I flew to Los Angeles with Imboden for a routine trip he was taking to different retailers that carry Jimmyjane. We started at Hustler Hollywood, an up-market sex emporium on a corner of the Sunset Strip, with a glass façade, bright lights and polished floors. Hard-core pornography was displayed just feet from an in-store coffee bar, arguably two things that should occupy different spaces, but the suggestion is to get over it. Presenting erotica stigma-free in the manner of a Barnes & Noble triggers the disorienting feel of a dark nightclub suddenly flooded with fluorescent ceiling lights, where everyone can see what you've been doing in the corner. But a fishbowl is precisely the metaphor of transparency Larry Flynt had in mind, and amidst this forthright statement of normalized sexuality (store motto: "Relax...it's just sex"), Jimmyjane is at home.

"With most other consumer products, like a pair of jeans, you have to convince people why they need it," Cory Silverberg, a certified sex educator and author who writes the Sexuality Guide for About.com, had told me. "With sex toys people come in already interested, and what you are doing is removing the obstacles. A lot of it is permission giving--saying that sex toys don't make you kinky, or that your boyfriend or girlfriend isn't good enough."

Imboden told me that Jimmyjane was the first to present sex toys in white packaging, and that retailers, accustomed to the candy-colored aesthetic, told him customers would never go for it. Several packages made by the company's competitors now have a cleaner, white look. Imboden picked one of them off a rack, and pointed out the words bullet-pointed on the package: body-safe materials, phthalate-free, waterproof. "You never used to see that," he said. European laws have driven much of the industry's attention to materials safety, but whether it is to be believed is something different. Sander Gardos, who founded MyPleasure.com, an online retailer of sex toys, had told me, "You cannot trust what's on the box--it has nothing to do with what's actually in there," recalling a manufacturer at a trade show in Shanghai who stood before a display of two boxes that contained the same product-- one was labeled "100% TPR" (thermoplastic rubber), the other "100% silicone"--and then admitted both were made with PVC. "We have visited the Chinese factories that make all the toys that say 'Made in Japan,'" Gardos said. "There are tremendous quality control issues in this industry because it is completely unregulated."

A stand-alone glass case carried what the salesman distinguished as the "sex devices"--superior quality, more nicely designed, and higher priced products "that don't crap out," as he put it. Jimmyjane's products occupied two shelves. The case also displayed products by LELO and Minna. On another shelf was OhMiBod's Freestyle vibrator, which pulsates to music from an mp3 player. It bore a striking resemblance to the Form 6, down to its solid plum color and narrow metallic band.

Nearby, in West Hollywood, we stopped in at Coco de Mer, a luxury erotic boutique with outlets in London and Manhattan. With Dave Stewart of the Eurythmics, who is an investor in the store, Imboden designed a custom version of the Little Chroma in black, with Stewart's lyrics etched into the aluminum and a leather cord threaded through the cap, along with a custom guitar pick. We then met Robin Coe- Hutshing at Studio BeautyMix, her store inside Fred Segal, in Santa Monica (which has since changed ownership). A wall behind the custom fragrance counter displayed Jimmyjane's vibrators, white porcelain massage stones (for which it won an International Design Excellence Award); and scented massage oil candles, which were the first candles of any kind to be formulated with a melting point matching body temperature, an innovation that makes them an effective emollient when poured onto the skin. In an environment of soaps, perfumes, and skin cream, Jimmyjane's bright color palette and white boxes fit as seamlessly as they had in a room of maid outfits and butt plugs. If Hustler Hollywood and Studio BeautyMix might represent almost dichotomous approaches to sex -- the excitement of sexual fantasy versus the everyday made sexy -- Jimmyjane works in both worlds by remaining agnostic.

We finished our tour in Venice, at A+R, the design store that Rose Apodaca, the former Women's Wear Daily editor, opened with her husband Andy Griffith. The store displays a compendium of home accessories from designers around the world. The Form 2 sits on a shelf behind glass wall display next to the Braun travel alarm clock by Dieter Rams, and is sometimes mistaken by customers, according to Apodaca, for a Japanese anime toy. In the adjacent case, beside colored glass vases in the shape of honey bears, are the Form 6 and Little Chroma. "We wanted to include these products in our mix because we wanted it to seem like a perfectly normal part of one's lifestyle," Apodaca told me. "Just like they'd have a great wine carafe or a filtered water bottle." When Sasha Baron Cohen walked into the store the week before I visited and learned what that Little Chroma was, he proceeded to browse the store picking up random objects and asking, "Does this vibrate?"

Victoria's Secret, a $5 billion retailer ubiquitous today in American shopping malls, was founded in San Francisco in the 1970s by a Stanford Business School graduate who felt embarrassed buying lingerie for his wife in a department store, and set out to create a more inviting atmosphere for men. Soon, picking up a vibrator in a shopping mall, or a store that sells home accessories, cosmetics or lattes may seem rather conventional. It nearly is already. One of the faster growing categories in terms of sales at Walgreen's, the nation's biggest drugstore chain, is sexual wellness. Walgreens has been selling a vibrating ring--a gateway sex toy--made by Trojan since 2006, except in the seven U.S. states where it is illegal to do so; Target and Wal-Mart sell them as well. Amazon.com currently carries just under 80,000 sexual wellness products. Sales of "sexual enhancement devices" in mass food and drug retailers (excluding Wal-Mart) increased by 20 percent for the year that ended April 15, according to SymphonyIRI Group, a Chicago-based market research firm. Yearly sales of sexual products through home-party direct sales, like Pleasure Parties, are more than $400 million. "Vibrators are already mainstream," said Jim Daniels, Trojan's former vice president for marketing, who estimates the market for vibrators in the US to be $1 billion--more than twice that of condoms.

Trojan, along with Durex and Lifestyle, are among the large companies now developing vibrators that a place like Walgreen's might start to feel O.K. about selling under florescent lights. Trojan has introduced the $60 Vibrating Twister--the condom maker's third vibrator model. For a trial, Philips Electronics launched a line of "intimate massagers" under their Relationship Care category. "These big multinational companies are realizing there is a ton money to be made," says Cory Silverberg. "They will change things more significantly than the political feminist sex stores and some of the more interesting manufacturers like Jimmyjane." Mainstream manufacturers and retailers are couching these products as being good for sexual health--that it's not just about getting turned on, or being kinky, but about being healthy, like exercising and eating well. "That's not exactly a change in our comfort with sex", says Silverberg--it still will be some time before sex toy ads become as acceptable as Viagra commercials--"it's a marketing ploy, but it will give people permission to try something they want to try anyway."

Johnson & Johnson's KY re-launched its own brand with what it's calling "intimacy enhancing products for couples," including a topical female arousal gel "scientifically proven to enhance a woman's intimate satisfaction." "I look at it as the final frontier of the women's movement," says Dr. Laura Berman, a prominent TV sex and relationships therapist who incited a vibrator buying frenzy after appearing on "Oprah" with various devices. "Women now feel more entitled and free to explore their own sexual responses."

As sex toys become just another personal electronic device, our expectations of them and how they are used are bound to change. Imboden has been considering this scenario for years already, quietly developing technologies that he says will "fundamentally alter the way that we interact with these products." Imagine wearable sensors-- embedded in clothing, or a bracelet--that operate according to heart rate, blood pressure and skin response. Imagine devices that communicate via a personal area network, connecting sexual partners in ways they don't even realize.

One afternoon at Jimmyjane's offices, Imboden told me that he believed the companies that will succeed in making sex toys are those that are forthright, trusted and accountable, like an intimate partner. He paused, then added -- "and give great orgasms" -- just before it became an afterthought.

Steeped in Tea

UTNE | The social significance of tea in America: how tea became the beverage of inner peace and armchair travel.

FIRST PUBLISHED IN UTNE, JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2007

ON A SUNNY APRIL MORNING in 1990, Mel Ziegler took a plane ride that changed his life. Ziegler, who founded and had recently sold Banana Republic, was flying back to San Francisco after attending a conference on values-driven business in Boston. Before its present incarnation as a 'casual luxury' clothing brand, Banana Republic marketed safari wear. Its retail stores were awash in ersatz Serengeti imagery-Jeeps, foliage, and fog-that used 'fantasy to lighten up the customers' idea of reality,' Ziegler would later write. Consumers indulged the story, and Banana Republic profited. On that April morning, Ziegler met a fellow passenger and young entrepreneur, Bill Rosenzweig. As they soared over the country, the men discovered their shared aspirations: personal transformation and capital gains. Tea, the two surmised, would be their salvation.

In the early 1990s, the domestic tea market was emerging from decades of mediocrity. A smattering of specialty tea companies-including Celestial Seasonings, Stash, Good Earth, Yogi, and Traditional Medicinals-had repositioned tea as a healthful and natural alternative to coffee and the lower-grade tea-leaf dust found in mass market bags of Red Rose and Lipton. Largely missing from the existing marketing, Ziegler believed, was the culture and experience of drinking tea. 'I am mad about tea,' he remarked at the time, and 'I can't think of a commodity more inappropriately marketed in the United States.'

The wine and coffee industries had recently proven that Americans with a gourmet palate would pay more for higher-quality beverages that came with a cultured air and complex aromatics. So with missionary zeal-and sensing an opportunity-Ziegler and Rosenzweig created a line of exotic blends (like Mango Ceylon), added whimsical taglines ('Metabolic Frolic Tea'), and packaged them in distinctive cylindrical tins loaded with a tantalizing aura of legend and mystery. Ziegler was appointed the Minister of Leaves; CEO Rosenzweig, the Minister of Progress. Life in the Republic of Tea, the name they gave their company, would be experienced 'sip by sip, rather than gulp by gulp.'

Today, the United States is looking more like the fanciful republic Ziegler imagined. Rooibos, chai, and yerba mate are joining kalamata olives, Sumatran coffee, and pinot noir in the mainstream American vernacular, as tea in its myriad manifestations becomes the ultimate healthy and modern beverage for millions, and a new American tea culture evolves at the speed that once characterized the country's romance with gourmet coffee.

Entrepreneurs are clamoring to capitalize on the tea renaissance. The number of tea shops has sprouted from some 200 nationwide a decade ago to more than 2,000. Taken together, annual sales of black, green, and now red and white tea have skyrocketed from $1.84 billion in 1990 to more than $6 billion in 2005 and are forecasted to reach $10 billion by 2010. Dozens of nascent companies jostle for a niche in the market's fastest-growing segment, specialty teas. Even skin creams and vitamin supplements containing EGCG, the lead antioxidant found in green tea, line supermarket aisles. And researchers, finding the mass media a conduit for their steady stream of findings on tea's health benefits, are confirming folk beliefs dating to the legendary moment when errant leaves of a nearby Camellia sinensis bush colored Chinese emperor Shen Nung's pot of boiling water in 2737 B.C. and the world's most consumed drink, after water, was accidentally discovered.

Tea may have been inappropriately marketed a decade ago, but today no other commodity is better poised to capitalize on a convergence of societal trends. In one marketing narrative, tea is touted as a multifaceted health aid and as a salve for those who wish to rebalance a life accustomed to speed. In another, it is pitched as worldly, gourmet, and, when it is organic and fair trade, even virtuous. In one moment tea acts as a social lubricant, and in the next it occupies the center of personal ritual. Taken collectively, these approaches reveal-as much as they deliberately and shrewdly exploit-the contemporary American social moment.

****

Americans may still be gulping life rather than sipping it, but more are opting for the latter. The legions of 'downshifters'-those who value time over money-'are growing, and mainstreaming,' says Juliet Schor, professor of sociology at Boston College and author of The Overspent American: Upscaling, Downshifting, and the New Consumer (Basic, 1998). When Schor first polled in 1995, 20 percent of Americans said they had made voluntary lifestyle changes, such as reducing the number of working hours and jobs, that resulted in their earning less money. In 2004, 48 percent said they had. Why? To reduce stress, most responded, as well as to have a 'more balanced life,' more meaningful or satisfying work, and a 'less materialistic lifestyle.'

'At various times throughout history,' boxes of Tazo tea read, 'Tazo has surfaced among the more advanced cultures of the day as a solution to the angst of daily life.' While Tazo marketing makes liberal use of historical license, more Americans are indeed opting out of the dominant consumer culture-the frenzied pace of life and associated angst, and inordinate concern for standard status symbols. The sociologist Paul Ray calls these people 'cultural creatives.' You might have seen them shopping at Whole Foods (rejecting the dominant consumer culture isn't tantamount to rejecting consumerism) or walking out of a yoga studio. Cultural creatives care about ecological sustainability, social justice, and self-actualization. They represent a countercultural movement that was born in the social upheaval of the 1960s and gathered a new generation of voices in the antiglobalization demonstrations of the 1990s.

If, over the course of our social history, coffee became bound up in the dominant American values of speed and productivity, then tea is now embraced as the opposing fuel, even as part of a lifestyle. 'For Americans,' argues historian James Norwood Pratt, author of The New Tea Lover's Treasury (PTA, 1999), 'tea represents a coffee recovery movement.'

On a December night in 1773, a group of Bostonians disguised as Mohawk Indians raided cargo ships docked in Boston Harbor and hurled chests of tea overboard. The Boston Tea Party marked an abrupt rejection of a beverage so integral to colonial life that John Adams, stopping at a tavern en route to sign the Declaration of Independence, asked whether it was 'lawful for a weary traveler to refresh himself with a dish of tea, provided is has been honestly smuggled and has paid no duty.' The landlord's daughter replied: 'No sir! We have renounced tea under this roof. But, if you desire it, I will make you some coffee.'

Thus the nation was born with a patriotic taste for tea's more caffeinated cousin. All across the young republic, coffeehouses opened as depots for political and philosophical discussion, becoming instrumental in the development of America's java-fueled urban work ethic. Nevertheless, tea remained entrenched in the national psyche. Some of the first American millionaires, T.H. Perkins, Stephen Gerard, and John Jacob Astor, all made fortunes trading tea with China, as clipper ships and railroads in the 1850s carried fresh tea to the New World and sold it through retailers like the Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company (A&P)-the nation's first supermarket chain. At the peak of consumption, in 1897, Americans each drank 1.56 pounds of it annually. (They now drink about half a pound each.)

Two innovations in the early 1900s revolutionized how Americans consume tea. Scrambling to attract attention in the summer heat at the 1904 World's Fair in St. Louis, exhibitors of Indian black tea poured hot brewed tea into glasses jammed with ice. The crowds came, popularizing a refreshing new beverage-iced tea-that Southerners already considered a major food group and that now accounts for around 80 percent of the way Americans drink tea. Four years later, New York tea importer Thomas Sullivan hand-sewed silk pouches to package samples of tea leaves for his customers. Enamored with the convenience of the bags, customers demanded that their product be delivered in them, too, and Sullivan replaced the silk with more economical gauze to create tea bags. Petroleum-based nylon mesh eventually became the standard, which some specialty companies are now flouting in favor of biodegradable material.

Up until World War II, Americans cherished green, oolong, and black teas. Home deliverers like the Jewel Tea Company routed tea across rural America. But Japan's invasion of China in 1937 abruptly cut off the country's lifeline to East Asian tea gardens and shifted American consumption almost exclusively to Indian black tea. (It would be 1978 before China reentered the U.S. market, and only recently have Americans appreciated green tea again.) Meanwhile, the Korean War forced producers to look to new, more stable sources of tea; Argentina emerged as one of the top suppliers to the United States. (The idyllic Argentine pampas grasslands will never find their way onto a box of specialty tea, however; most of the low-quality leaves grown there are still used for iced tea or for multiple-source, mass market black tea blends.) At three dollars for 100 bags, tea became a supermarket 'loss leader'-a product sold below cost. For consumers, it lost luster.

A 1983 New York Times editorial, 'Tea Snobs and Coffee Bigots,' summed up the degraded perception-and popular associations-of tea at the time. Responding to a letter from a Portland woman who complained about 'New York's lack of civility concerning the serving of tea,' the editors opined that 'Coffee Bigots . . . think it is somehow un-American or unmanly or troublemaking to drink tea-and scorn those who do as Tea Snobs. This bigotry, fortunately, seems to be diminishing as more and more drinkers of decaffeinated coffee also speak up for their special taste.'

A popular countermovement to caffeine had been brewing for over a decade in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, where a young man named Mo Siegel was picking wild herbs near his home in Boulder, Colorado. Amid a growing wave of natural foods introduced in the 1970s, Siegel wanted to offer Americans a healthy beverage as an alternative to the wan coffee brews favored by his parents' generation and the handful of specialty black teas-mostly Lipton, Twinings, and Bigelow's Constant Comment-then on supermarket shelves. Siegel faced stiff resistance peddling his novel herbal tea blends, which he called Celestial Seasonings. The buyer for a major supermarket chain-Siegel declines to say which one-once threw a box of Red Zinger against a wall and kicked him out of his office. Lipton's head tea taster at the time belittled herbal teas as 'weeds by the swamp.' (Lipton is now one of the world's largest producers of herbal teas.)

Printed with colorful pictures and New Age quotations, Celestial Seasonings boxes eventually found their way into millions of households and reintroduced Americans to the personal and social ritual of drinking tea. Blends like Egyptian Chamomile also helped reclaim tea's exotic character, imagery that goes a long way in the marketing of specialty tea today. Roastaroma offered a crossover for curious coffee lovers, and others like Sleepytime established tea as a beverage with an occasion-and also a function-for drinking at different times of the day.

Celestial Seasonings helped pave the way for the tsunami of ready-to-drink teas that swept into the market next. In 1987 Snapple introduced bottled iced tea with an 'all natural' tagline on labels that, ironically, depicted the Boston Tea Party. Now accounting for one-third of domestic tea sales, and composing the single largest segment of tea, ready-to-drink teas sate Americans' desire for health, convenience, and speed of delivery. Many of us do want refreshing and calm, but we still want it on the go. While most teas on the market are still brewed with low-grade tea leaves, today's fertile crop of specialty tea brands and dedicated tea shops introducing higher-grade loose leaf blends are raising the standard once set by the lowly mass market tea bag.

The events of that December evening in Boston may have initially served as a symbolic rejection of British influence and authority, but they ultimately allowed American society to write its own circuitous social history with tea-to eventually reclaim a foreign drink with a foreign set of cultural practices as its own. Sipping a cup of tea today provokes a mix of imagery, some of it still an antiquated and imagined notion of imperial England or China, but much of it an amorphous global fusion endemic to nowhere in particular. We drink herbal teas even when we're not sick. We make lattes out of green tea. We have taken the symbols of traditional tea cultures-chai on the streets of Delhi, oolong tea in a Beijing teahouse, afternoon tea service in London, chats around the samovar in St. Petersburg-and, through a process resembling the construction of an ethnic food court in a shopping mall, put them under one proverbial roof.

****

To the would-be traveler lugging a shopping basket, a supermarket shelf of tea today is as bewildering (and enticing) as the pages of an adventure travel company catalog. Navigating all the worldly choices, one might arrive at a box of Numi Tea's Rainforest Green, depicting a lush cascade that invites an armchair excursion into an Australian rainforest. Down the aisle, Republic of Tea's tin of rooibos evokes the arid South African bush. Nearby, Stash Tea's Exotica blends beckon 'adventurous sippers' to explore 'the essence of distant places . . . tropical hillsides . . . monsoon-swept plains . . . the foothills of the Himalayas.'

Starbucks seduced coffee drinkers by 'romancing the bean' and creating a lexicon of foreign words that heightened customers' sense of sophistication and transported them to an imagined continental culture. Bottled water gets by on the tap water fear factor and a certain trendy appeal, but also on consumers' attraction to distant mountain springs so pure that they couldn't possibly be chlorinated.

Going further, specialty tea companies market wanderlust, packaging a tantalizing and educational blend of exotic locales and rich cultural traditions. Just as Sri Lankans might drink Coca-Cola and eat McDonald's to taste modernity, Americans sip Ceylon tea to taste the exotic. And specialty tea companies invent blends that deliberately evoke an unlikely-and inauthentic-melding of geographies and cultures to meet consumers' desire to be transported. For example, Mighty Leaf Tea's trademark blend, Green Tea Tropical, includes 'notes that conjure up a sense of escape to a tropical island,' says Mighty Leaf's founder and CEO, Gary Shinner. One small but successful company, Zhena's Gypsy Tea, bases its marketing on the founder's Ukrainian heritage-a heritage that is not known for its tea but that contains just the right dose of exoticism. 'Specialty tea is being driven by consumers' desire to learn more of the world,' says Joe Simrany, president of the Tea Association of the USA.

If a Sumatran latte no longer evokes the mystique it once did before Starbucks saturated the American landscape, the display of Tazo tea-which the company purchased in 1999-featured on the chain's counters might serve to reclaim that aura. Tazo is one of the fastest-growing brands of specialty tea in North America. Its original marketing at Starbucks used images of Sikhs, Chinese, and Britons blissfully sipping cups of Tazo. Indeed, the Tazo brand was conceived as a 'combination of cultures drawn together,' explains Steve Smith, Tazo's founder and vice president of tea. 'Our goal was to have the brand look like it was from there and then, not here and now,' using ambiguous symbology 'to appeal to people who are into discovery.' Never mind the reality of these exotic destinations-you're more likely to sip chai in India on the sidewalk of a filthy street than in monsoon-swept serenity-but marketing isn't about reality, of course, just as an adventure travel catalog listing for 'Seven Days on the Silk Road' says nothing about poverty or, for that matter, diarrhea.

The wave of specialty tea companies founded in the early 1990s coincided with a rising tide of Americans traveling to the mystical realms found on their packages. Countries such as Bhutan opened their doors and Americans set out to explore new frontiers rather than just imagine them. An 'adventure travel' industry expanded to satisfy Americans'-especially baby boomers'-'hunger for authentic experiences . . . to leave the clinical corporate environment and touch something real,' says Kevin Callaghan, CEO of Mountain Travel Sobek, a pioneer in the industry. Over time, more tourist infrastructure and services have made farther reaches of the world more accessible and attractive. In 2005 a record number of U.S. travelers ventured abroad. No longer, tour operators say, do these American travelers want to simply get to a destination, they want an experience-and in recent years travel companies have scrambled to meet that wish for more in-depth activities. Today's vacationer wants authenticity, healthy activity, and meaningful engagement. To this increasingly mainstream American consumer, and the three-quarters of Americans who don't have passports, Steve Smith would like to offer a pot of tea.

****

The administrative capital of the Republic of Tea occupies the ground floor of a standard-issue suburban office park building outside Novato, California, north of San Francisco. Inside, soft yellow walls color a few rooms of cubicles arranged by a feng shui master. An enormous display case near the front door is stocked with the company's dizzying array of tea-related products, which include Stir Fry Tea Oil, Jerry Garcia Artisan Tea, and rooibos-based blends like Get a Grip Herb Tea for PMS/Menopause No. 4. (Where is this all headed?)

One morning last August, various 'ministers' holding metal spoons congregated in the office kitchen around two small bowls of tea. The company had decided it needed a 'relaxing tea,' and these tasters were evaluating candidates for a reformulated version of an existing brand, Zen Dream Tea. Each bowl contained lemon balm, lavender, chamomile, and valerian, in different concentrations. The ministers dipped their spoons, sniffing and slurping the tea, commenting on taste and calming profiles.

Mel Ziegler sold Republic of Tea less than two years after he founded it, but his self-reflective book chronicling those years, Republic of Tea: Letters to a Young Zentrepreneur (Doubleday, 1992), commands near-biblical reverence at the company and is required reading for new employees. 'It carries the spirit of why we exist-the philosophy behind who we are,' says Minister of Commerce (national sales and education) Barbara Graves, adding, 'but we're really not a cult!'

For millennia, tea has been bound up in ritual, often occupying the center of ceremonial practices. And ritual is the essence of religion, defined as a set of practices that divide the world between the sacred and the profane (or everyday), in the process creating a community or social experience. Tea companies strongly market the ritual consumption of tea-'take the tea transformation,' Numi tells consumers. They provide instructions on how to prepare it, and when to drink it. 'They're talking about creating a type of sacred space,' notes Brown University professor of religion Mark Cladis. 'The ordinary or everyday is that hectic, fast-paced way we live our lives. Tea upsets this routine, introducing the sacred moments where we can be mindful of who and where we are, where schedules have disappeared momentarily.'

In 1994 Steve Smith introduced Tazo tea in Portland, hailing the company as 'The Reincarnation of Tea.' Inspired by brass rubbings on churches, Smith incorporated cryptic symbology in the Tazo logo. He describes the alchemical process of creating blends such as Om and Zen, initiated by unconsciously scribbling formulas down on a yellow pad, as less mad scientist than 'channeling the tea shaman.' Smith packaged the teas in text-heavy boxes loaded with jibberish and obscure signatures and equations-'our version of the Rosetta stone,' he says. The intention may have been whimsical, but Smith admits an alternate purpose in Tazo's manufactured mysticism. 'Life is about the detail,' he explains. 'You miss the detail, and where are you? We try to drop in little bits and pieces that will pay back when you dig into it and make you think. In this day and age, you find your spirituality where you can.'

But most Americans are not finding their spirituality in a cup of tea, of course-for many, it's just a tasty beverage and a way, they hope, to live longer. However, with gimmicky, pop-spiritual marketing, Smith and his peers in the industry are attempting to attract a population that is searching. The fabric of American communities and families has frayed in recent decades, some sociologists argue, and recent studies identify a population that is ever more socially isolated. Where Americans once found purpose in community, their appetite for meaning is being played out in a search for unorganized spirituality or the rediscovery of religion in many forms, including evangelicalism. Even society's rediscovery of tea has taken on a 'born again' character, exhibited foremost in the fervor of the founders of this generation of specialty tea companies, many of whom arrived at tea later in life and now extol it as a life-transforming force. If, for most Americans, tea doesn't provide meaning and order, then at the very least, a soothing, healthful beverage 'is very comfortable at a time when the world is increasingly uncomfortable, unpredictable, and dangerous,' says sociologist Juliet Schor. 'Tea feels safe.'

All the whimsy and marketing mystique that companies craft into specialty tea brands boils down to a matter of consumer taste. (After all, they're selling a beverage.) To appeal to Americans' insatiable thirst for new varieties, and to satisfy palates unaccustomed to tea's subtle flavor nuances-which could otherwise seem plain or, if the tea is improperly brewed, bitter-specialty tea companies load on the flavor (increasingly using natural ingredients as opposed to the sprays and oils mass market brands employ). Flavored teas aren't an exclusively American twist. Jasmine and Earl Grey blends have long been favored around the world. But we prefer much sweeter and stronger flavors, notes Wei Huang, the Chinese American owner of Arogya, a tea shop in Westport, Connecticut. 'Americans put soy sauce on plain white rice and use sugar to sweeten green tea-you wouldn't see this in China,' she says. Companies usually add these flavors to inferior leaves. However, across the board, remarks tea expert Norwood Pratt, today's specialty brands 'are now providing 'premium' tea in contrast to the 'ordinary' tea bag quality.'

****

Tea and coffee have long represented a great yin-and-yang duality. In The World of Caffeine (Routledge, 2001), authors Bennett Alan Weinberg and Bonnie Bealer lay out these opposing aspects: Coffee is male; tea is female. Coffee is boisterous, hardheaded, and down-to-earth; tea is decorous, nurturing, and elevated. While coffee is associated with work and passion, tea reflects spirituality and contemplation.

In light of coffee's historic associations, it comes as no surprise that it became the symbol for the defiant American revolutionaries. More than two centuries later, a kinder, gentler revolutionary spirit continues, playing out-naturally, as goes America-in the marketplace. 'An impetus for me in designing Numi's packaging was to infuse the most mundane activity, walking through a grocery store, with the sublime and rich in self-reflection,' says Numi Tea co-founder Reem Rahim. 'What other way to subversively create a revolution-in this sense, a spiritual revolution-than through art and tea? I believe that tea, and art, are part of a feminine energy that is starting to permeate through our shift in consciousness.'

Rahim's desire to redirect society sounds markedly similar to another cultural creative's mission for his own company. 'Our secret and subversive agenda,' Mel Ziegler wrote about founding the Republic of Tea, 'was to bring Americans to an awareness of 'tea mind,' in which we would all come to appreciate the perfection, the harmony, the natural serenity, and the true aesthetic in every moment and in every natural thing.'

But as Schor, Ray, and others point out, American society is evolving to that place anyway, becoming a little more yin, a little less yang; a little more feminine, a little less masculine; a little slower, a little less fast. The course tea has taken in this country-rejected one brisk evening in Boston, regarded as 'unmanly' and 'un-American,' and now embraced, at least in part, as a backlash to the dominant social paradigm dating from that historic event-may reflect a young society maturing. 'Perhaps the exercise in moving from Banana Republic to the Republic of Tea,' Mel Ziegler pondered, 'is all only a projection of my own slow process of growing up.'

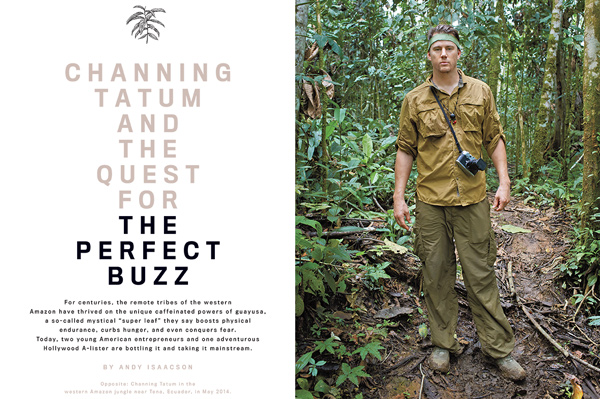

Channing Tatum and the Quest for the Perfect Buzz

MEN'S FITNESS | How two young entrepreneurs and one Hollywood A-Lister, with the help of a caffeinated Amazonian “super leaf,” are trying to shake up the $30 billion energy-drink market with a healthier alternative.

FIRST PUBLISHED IN MEN'S FITNESS, MARCH 2015

CHANNING TATUM HAS A RECURRING DREAM in which he sprints furiously across an unfamiliar landscape, then, arms outstretched, takes flight, soaring above the terrain like a hang glider. A version of this dream comes to him one night in spring of 2014, while dozing in a hammock deep inside Ecuador’s rainforest. This time he runs up a hill dotted with tall trees. At the crest stands a forbidding wall that rises as he draws nearer. Barefoot, he bounds up the wall and, reaching the top, sees a vast territory unfurling toward the horizon. He pauses, then plunges down the other side.

The next morning Tatum recounts the details of the dream to a group of us sitting on tree stumps around a smoldering fire, in a remote indigenous Sápara settlement near the border of Peru. The villagers have painted our cheeks with a reddish pigment made from tree seeds, issued us each Sápara names (Tatum takes “Tsamaraw,” which means “protector spirit”), and blown tobacco smoke into our faces to expel negative energy.

In our hands are coconut shells that contain a caffeinated elixir we’ve traveled 4,000 miles to find: guayusa, a plant native to the western Amazon, whose green, elliptical leaves have been a staple of the region’s indigenous populations for thousands of years.

The Sápara drink guayusa (“gwhy-YOU-sa”) for stamina, and as a tool to interpret dreams. Shipibo medicine men in Peru prescribe a strong, guayusa-based drink to patients who suffer from trauma, as a way to conquer fear. The Kichwa people, in Ecuador’s northern jungle, say the plant also kills hunger, and often pack guayusa leaves as their only sustenance on long hunting expeditions.

A Kichwa man had described to me the mystical circumstances surrounding the discovery of the plant’s energy-boosting properties. It was during an era of tribal warfare; one night the spirit of a tree told a sleeping Kichwa sentinel, “Hey friend, I can help you.” The sentinel awoke to find a bush rustling nearby. He chewed its leaves, and immediately felt alert and animated. Today the Kichwa refer to guayusa as “the night watchman’s plant.”

Tatum, the star of Foxcatcher and this summer’s Magic Mike XXL, has come to the Amazon to sample the plant for a different reason. An investor in the New York-based beverage startup Runa (a Kichwa word meaning “fully alive”), the first company to produce drinks containing guayusa, he wants to learn everything there is to know about it. We’ve spent the last few days with Runa’s co-founders, Tyler Gage and Dan MacCombie, drinking, farming, and literally bathing in guayusa as women pour bucketfuls over our heads.

Gage and MacCombie represent the latest entrepreneurial rush into the rainforest—a place from which, in recent years, marketers have emerged with billion-dollar beverage products like açai. Leveraging Tatum’s celebrity, the pair hope to break into the $30 billion energy drink market, a field dominated by Red Bull and brands like Monster Beverage, which has concocted a juggernaut out of guarana, another caffeinated Amazonian plant. Trouble is, unlike guarana, few people have heard of guayusa. Tatum, Runa’s unofficial spokesman (his exact role is still being hashed out), hopes to change that.

After Tatum finishes describing his dream, a soft-spoken Sápara man focuses on him: “Your running represents the instinct of always striving to go further,” he says. “By making it to the top, you made it in your personal, professional, and spiritual life—there is nowhere else to go. But that expanse on the other side: That is the platform to recognize who you truly are.”

I wait for Tatum to lighten the mood. After all, this is the Jump Street star whose dick jokes have gone viral. He’s also a well-known prankster off camera. In fact, earlier this trip, he yanked me from a raft into a fast-flowing river and goaded me into eating a squirming grub from a palm tree. I expect him to respond to this shamanic psychoanalysis with a self-deprecating joke.

Instead Tatum nods along earnestly, pauses, then takes a sip from his coconut shell and launches into yet another dream, about waking up in a room from which he can’t escape. “This happens a lot,” he begins, “and I wonder what it means...”

The day before, at Runa’s factory in Archidona, Ecuador, Gage, MacCombie, Tatum, and his producing partner, Reid Carolin, take a tour of the company’s guayusa factory. Inside a low-slung white building covered in plastic, a woman in hospital scrubs and a surgical mask stirs beds of leaves, allowing them to dry and oxidize. They smell pleasant, like freshly cut grass, and Tatum snatches a pile and burrows his nose in it. He and Carolin first discovered Runa at a Whole Foods in New Orleans while shooting 21 Jump Street, in 2011, and the drink became their lifeblood as they raced to finish the Magic Mike script. “We were hammering it like it was a drug,” says Tatum. “Runa went in smooth and left smooth, and gave a longer buzz than coffee.” He now starts every day with a can of it. The next morning, I watch as he slams one then backflips off a 50-foot bridge into a river.

An 8.4-oz can of Runa’s energy drink comes in two flavors: Berry, with 17 grams of sugar, and Original Zero, a sugar-free version. Both have 120 milligrams of caffeine from guayusa leaves, which are dried in Archidona, shipped to a facility in New Jersey, then brewed into the carbonated energy drinks as well as a line of glass-bottled teas flavored with mint, hibiscus, and lemongrass.

Before Gage and MacCombie launched their company, not a single scientific paper had been written about guayusa. The Kichwa people say the plant can replace food on lengthy jungle trips. Both Gage and Tatum say that after drinking guayusa, they feel a pleasant boost without the jitters coffee gives them. “I needed something that gave me a longer burn and didn’t leave me cracked out,” says Tatum. Gage recalls a curious sensation the first time he drank guayusa. “I felt very awake but rooted at the same time,” he says. “I wasn’t sure why, but it was striking to me.”

Recent research conducted by Applied Food Sciences, a U.S. supplement firm that plans to market guayusa extract, offers evidence to support the “slow burn” claim. The plant is part of the holly family, and appears to offer the virtues of both tea and coffee: Its leaves contain significant levels of various antioxidants, including the catechins found in green tea, which reputedly fight cancer and boost metabolism, and the chlorogenic acid in unroasted coffee beans, which spurs weight loss by slowing the uptake of glucose from the intestines.

In addition to natural caffeine, guayusa also contains theobromine, a stimulant abundant in chocolate. Ounce for ounce, there’s less caffeine in guayusa than in dark roast coffee, but for reasons not yet well understood—having to do with the synergistic effects of these various compounds—the body metabolizes the caffeine in guayusa over a longer period of time.

“For endurance athletes who’d like to have more of a sustained release if they’re doing something more than a quick run—this really helps for that,” says Chris Fields, vice president of scientific affairs at Applied Food Sciences, which is starting clinical trials to investigate guayusa. “It’s a really unique plant, and now we seem to understand why it’s been used for centuries by Amazonian groups—it has so many medicinal benefits.”

Guayusa lacks tannins, the compounds in green and black tea that give it its bitter, puckery quality. When I drink a 14-oz bottle of Guavo Zero Unsweetened Runa, it tastes like watered-down tea. The first thing I notice sipping an 8.4-oz can of Runa Original Zero (with a hint of lime) is a sharp acidic tinge of artificial lime that instantly dissolves into a leafy, tea-ish aftertaste. The fizzy, one- two punch reminds me more of a store-bought Arnold Palmer than it does a syrupy Red Bull. (This is not a bad thing.)

Guayusa’s energy kick is gradual, more tortoise than hare. After one serving, I feel a subtle caffeine lift, rather than a spike. (For those who rely on the jolt of a Grande Pike Place or Monster, take note.) Two servings later, though, my body feels alert, and I’m humming along like a machine. I can see why Tatum and Carolin drink it during script-writing marathons. “The whole reason we [embraced Runa],” says Carolin, “was because we saw the effect this product had on our creativity.”

By offering a product with this unique rush, and by touting its claim of clean energy, Runa hopes to muscle into a marketplace cluttered with less healthy choices. The definition of “energy drinks” is somewhat elastic—they’re marketed as dietary supplements—but all tend to share large doses of caffeine combined with taurine, glucuronolactone, carnitine, B vitamins, and ginseng, various forms of stimulants, which, in excess, can give rise to harmful side effects. Most energy drinks also pack lots of sugar. An 8.4-oz can of non- diet Red Bull has nearly seven teaspoons of added sugar. (The American Heart Association advises no more than nine teaspoons of added sugar a day for men.)

Though the health effects of all the various chemical and herbal ingredients used in energy drinks and their possible interactions with caffeine are largely untested, the consequences of excess caffeine consumption are well understood: tachycardia, arrhythmia, hypertension, seizures, insomnia, and anxiety. According to the Center for Science in the Public Interest, a health advocacy group, FDA documents show that in the past decade, 34 deaths have been linked to, and possibly caused by, energy drinks. “Energy drinks are clearly causing symptomatic arrhythmias,” says Stacy Fisher, M.D., director of complex heart diseases at University of Maryland School of Medicine. Market research firm Mintel reported last year that nearly six in 10 Americans who consume energy drinks or shots—mostly 18– to 24-year-olds—say they now worry about their health.

“Right now, our low-hanging fruit is reluctant Red Bull drinkers who are like, ‘I drink this stuff but I know I shouldn’t, I know there’s something better’—which I think is a huge audience,” Gage says. “We just need to communicate in the right way to get them.”

Guayusa had never been grown commercially until five years ago, when Gage and MacCombie, two friends from Brown University, began shipping bags of the leaves to the U.S. Today Runa is sold in 7,000 stores across the country, including Safeway, Whole Foods, and Vitamin Shoppe. Last year, the company took in $2 million in sales; this year it’s on track to make $8 million. Runa has also attracted an eclectic mix of investors, including responsAbility, a Swiss sustainable management fund; a successful musician and producer named Dr. Luke; and the founder of Zico coconut water, Mark Rampolla.

Another investor, New York artist Neil Grayson, who’s a friend of Tatum’s and knew of the actor’s taste for Runa, connected him with Gage in 2013. Tatum immediately noted an auspicious coincidence: The character he’d played in his 2006 breakout film Step Up was also named Tyler Gage. If for no other reason, he tells me, “the sheer sake of weirdness” piqued his business interest in Runa.

Gage first tasted guayusa in 2005, after his freshman year in college, when he was in Costa Rica doing research with an American ethnobotanist. At the time, Gage, who’d been recruited to play soccer at Brown, was obsessed with health, nutrition, and peak performance. He’d tried going vegan for 18 months and Paleo for a spell, and even experimented with lucid dreaming. “I was interested in what the human mind has the capacity to do,” he says.

Eventually Gage came upon books by a decorated triathlete named Mark Allen, who’d studied the teachings of a Huichol shaman from Mexico. “He was relatable to me, from an athletic performance point of view,” says Gage, who reached out to Allen after his freshman year. “This wasn’t a dude who believes in spirits and wooah. No—homie won the freaking Ironman six times, and he attributes his success to the strength he learned with shamanism.”

Gage studied with Allen, who inspired him to study plant medicine in the Peruvian Amazon. There, for college credit, Gage researched the ethnolinguistics of the Shipibo people, while the Shipibo shamans put him through intensive ceremonies and diets. “Every day I had to get up at sunrise, drink these gnarly plants, and basically sit out in the jungle by myself,” he says. “It was really intense and really cool. And I can’t really explain it, but that’s when I remember feeling things shifted inside me.”

When Gage got back to Brown, his friend MacCombie was enrolling in a class on social entrepreneurship; he dragged Gage along. The course required that they write a business plan. In Peru, Gage had seen how Amazonian communities are often drawn into business with oil and logging companies for lack of any economic alternatives, so the two conceived of a company selling a guayusa-based beverage. As far as they were concerned, it was a class exercise. But their professor—an entrepreneur named Danny Warshay, who’d worked for Duncan Hines—urged them to think otherwise. “It hadn’t even crossed our minds,” Gage confesses. Over late nights, however, the idea marinated. In December 2008, two days after he and MacCombie graduated, they flew to Ecuador.

After six months of backpacking among villages to secure guayusa suppliers, Gage and MacCombie landed a $50,000 small business grant from Ecuador’s Ministry of Export, which in 2010 they used to build Runa’s first research facility, a steel drying-chamber in a bamboo garage full of chickens. Larger grants from the Ecuadorean government and the U.S. Agency for International Development allowed them to build the first real Runa factory. They shipped guayusa back to the States and managed to sell the first boxes to Whole Foods. At a natural foods trade show in 2011, Gage and MacCombie were hawking samples of their “Amazonian tea” from a remote corner booth when Neil Kimberley, former brand director at Snapple, happened by and offered to help formulate their product. “You guys seem pretty cool,” he told them. “Give me a call.” He’s now on Runa’s board of advisors.

Today, Runa’s harvest comes from over 3,000 local farmers, who tend the bushy plant in traditional gardens called chakras. The company’s also launched a nonprofit that funds the largest reforestation program in the Ecuadorian Amazon, partly supported by the MacArthur Foundation, and is also helping guayusa farmers form cooperatives.

We’re sitting on a grassy airstrip beside another Sápara settlement when Gage reaches into a cardboard box and pulls out a few prototypes of the Runa energy drink can, which prominently features a guayusa leaf and the words “Clean Energy.” One of Runa’s investors, Kim Jeffery, who, as the president and CEO of Nestlé Waters North America, had helped turn it into the continent’s third-largest beverage company, has advised Gage on the importance of a clear, succinct message. “His thing is: You have three seconds to tell people what your product is,” Gage says. “What we want people to say about Runa is not that it’s tea, or light tea, but that it’s better than tea. Categorically better, and categorically different.”