Return of the Fungi

MOTHER JONES | Paul Stamets is on a quest to find an endangered mushroom that could cure smallpox, TB, and even bird flu. Can he unlock its secrets before deforestation and climate change wipe it out?

Paul Stamets with agarikon. Photo by: Andy Isaacson

FIRST PUBLISHED IN MOTHER JONES, NOV-DEC, 2009

In the old-growth forests of the Pacific Northwest grows a bulbous, prehistoric-looking mushroom called agarikon. It prefers to colonize century-old Douglas fir trees, growing out of their trunks like an ugly mole on a finger. When I first met Paul Stamets, a mycologist who has spent more than three decades hunting, studying, and tripping on mushrooms, he had found only two of these unusual fungi, each time by accident—or, as he might put it, divine intervention.

Stamets believes that unlocking agarikon’s secrets may be as important to the future of human health as Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillium mold’s antibiotic properties more than 80 years ago. And so on a sunny July day, Stamets is setting off on a voyage along the coastal islands of southern British Columbia in hopes of bagging more of the endangered fungus before deforestation or climate change irreparably alters the ecosystems where it makes its home. Agarikon may be ready to save us— but we may have to save it first.

Joining Stamets on the 43-foot schooner Misty Isles are his wife, Dusty, a few close friends, and four research assistants from Fungi Perfecti, his Olympia, Washington- based company, which sells medicinal mushroom extracts, edible mushroom kits, mushroom doggie treats, and Stamets’ most recent treatise, Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save the World. “What we’re doing here could save millions of lives,” he tells me on the first morn- ing of the three-day, 120-mile voyage. “It’s fun, it’s bizarre, and very much borders on something spiritual.”

A few months earlier, the University of Illinois-Chicago’s Institute for Tuberculo- sis Research sent Stamets its analysis of a dozen agarikon strains that he’d cultured in his own lab. The institute found the fungus to be extraordinarily active against XDR-TB, a rare type of tuberculosis that is resistant to even the most effective drug treatments. Project BioShield, the Depart- ment of Health and Human Services’ bio- defense program, has found that agarikon is highly resistant to many flu viruses in- cluding, when combined with other mush- rooms, bird flu. And a week before the trip, the National Center for Natural Products Research, a federally funded lab at the University of Mississippi, concluded that it showed resistance to orthopox viruses including smallpox—without any apparent toxicity. The potential implications are ob-vious: Most Americans under 35 have notbeen vaccinated for smallpox, and expertsfear the current supply of the vaccine maybe insufficient in case of a bioterror attack.A bird flu pandemic within the decade iseven likelier. Currently, agarikon is beingtested to see if it can also fight off the H1N1swine flu virus.

“When you mention mushrooms people either think magic mushrooms or portabellas. Their eyes glaze over,” Stamets laments. That a homely, humble fungus could fight off virulent diseases like smallpox and TB might seem odd, until one realizes that even though the animal kingdom branched off from the fungi kingdom around 650 million years ago, humans and a fungi still have nearly half of their DNA in common and are susceptible to many of the same infections. (Referring to fungi as “our ancestors” is one of the many zingers that Stamets likes to feed audiences.)

On the first morning of our journey, agarikon remains elusive. From the deck of the Misty Isles, the white heads of bald eagles pop out of the dense green slopes of Mink Island, generating false sightings of H the chalky mushroom in the treetops. “People say, ‘Everywhere you mycologists look, you see mushrooms,’” Stamets says, focusing his binoculars. He laughs. “It’s true. The thing about mushroom hunters is, they tend to burn an image of a mushroom on their retina. Then you end up overlaying that image on the landscape. The mushrooms seem to jump out at you.”

STAMETS is of medium height and stocky build. His graying beard, round face, and glasses recall Jerry Garcia. As he tells it, mushrooms came into his life because of a humiliating stuttering habit. “I always stared at the ground and couldn’t look people in the eye,” he recounts. “That’s how I found fungi.” He remembers pelting his seven-year-old twin brother with puffball mushrooms, watching the spores explode in his face. But Stamets didn’t get serious about mushrooms until he was 18, when he ingested psilocybin mushrooms for the first time. Hallucinating alone in the Ohio countryside, he got caught in a summer thunderstorm and climbed a tree for shelter. Waiting out the storm, Stamets examined his life. “I asked myself, ‘Well Paul, why do you stutter so much?’ So I repeated, ‘Stop stuttering now,’ over and over again, hundreds of times. The next morning, someone asked, ‘Hi Paul, how are you?’ I looked him right in the eye and said, ‘I’m fine, how are you?’ I didn’t even stutter. That was when I realized mushrooms were really important to me.”

Not long after his first trip, Stamets enrolled in college but dropped out to work as a logger. He eventually graduated from Olympia’s Evergreen State College, whose unofficial motto, Omnia Extares, roughly translates as “Let it all hang out.” While studying biology and electron microscopy, he pioneered research on psilocybin, dis- covering four new species and writing a definitive field guide. Unable to afford grad school, Stamets started Fungi Perfecti and published The Mushroom Cultivator, which remains a classic within the subculture of mushroom enthusiasts. (He once spotted a copy on the bookshelf of one of the directors of the Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.)

Stamets began distancing himself from the magic mushroom crowd about nine ears ago. “The problem with the psychedelic scene,” he told me while driving near his vacation home on Cortes Island, the Grateful Dead playing on the stereo, “is that people contemplate their belly but- tons and don’t get anything done. I wanted to save lives and the ecosystem.” Yet he still credits psilocybin with giving him a sense of purpose. Stamets, who has a black belt in Tae Kwon Do, used to spend hours executing complex martial arts routines in the mountains as he tripped. “I had these visions of myself as a mycological warrior in defense of the planet.”

While studying the medicinal uses of fungi, Stamets built an extensive library of wild mushroom cultures harvested from the virgin forests of the Pacific Northwest. “It’s my most valuable asset,” he says. In the event of a fire, “everything can burn. I’m grabbing my test tubes and running.”

His tinkering has yielded many surprising discoveries about mushrooms and mycelium, the cobweblike, often hidden network of cells that spawns them. He’s demonstrated that oyster mushroom mycelium can more effectively restore soils polluted by oil and gasoline than conventional treatments can; in one eight-week experiment, the fungus broke down 95 percent of the hydrocarbons in a diesel- soaked patch of dirt. He’s used sacks of woodchips inoculated with oyster mycelium as filters to protect river habitats from pollutants such as farm runoff contaminated with coliform bacteria. Recently, he proved that cellulosic ethanol could be produced with sugars extracted from decomposing fungi.

Insisting that he’s merely a “voice for the mycelium,” Stamets says he can’t re- ally take credit for his discoveries about an extraordinarily diverse and evolutionarily successful kingdom that modern science has scarcely explored. Still, over the past four years, he has filed for twenty-two patents and received four. “I’m up against big bad pharma, and they will try to steal from us. I have no illusions about this,” he says. “Truly, it’s a David versus Goliath situation.” He asserts that after one of his public talks, in which he spoke about his discovery of a fungus that kills carpenter ants and termites by tricking them into eating it, he was approached by two retired pesticide industry executives. Convinced that their former employers would feel threatened by this relatively cheap, nontoxic pesticide, Stamets claims, they advised him to watch his back.

Stamets’ mother, a charismatic Christian, believes the only explanation for his unexpected discoveries is that he is chosen. “I’m not that smart,” he says. “I was the dumbest one in my family. But I’m just exceptionally lucky. Other mycologists know more about mycopesticidal fungi than I do. They missed it. In the 2,000-year history of Fomitopsis officinalis”—agarikon’s scientific name—“I’m the first one to discover it has antiviral properties? I don’t get it, either.”

“Paul Stamets is a modern example of the amateur scientist from the 17th and 18th century who made wonderful contributions with only their native curiosityand keen sense of observation,” explains Eric Rasmussen, a former Navy physicianand researcher for the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and the National Science Foundation, who now heads Instedd (Innovative Support to Emergencies Diseases and Disasters), a Google-funded nonprofit that develops technology to control disease outbreaks. “He’s listened to in a lot of unexpected corners.” In 1997, Battelle, a nonprofit R&D lab and a major Defense Department contractor, asked to screen more than two dozen strains of Stamets’ fungi. A few years later, it sent him back a classified report revealing the mushrooms to be highly effective in breaking down the neurotoxin VX, the illegal chemical weapon. Soon afterward, DARPA invited Stamets to one of its brainstorming sessions.

In his role as an ambassador for an en-tire taxonomic kingdom, Stamets has bee nelevated to something of a cult figure. “Ido have some crazies once in a while who believe that I’m the messiah or that we’re destined to be together,” he said, by way of explaining the tight security around his Olympia compound. “That’s sort of unnerving.” While we explored Cortes Island the day before setting sail, he occasionally texted with Leonardo DiCaprio, who had featured Stamets in his documentary The 11th Hour. Anthony Kiedis, the singer of d the Red Hot Chili Peppers, had planned to join the agarikon expedition until he broke his foot. Stamets has “hero status in t my mind,” Kiedis emailed me. “He opens himself up to information about fungi the same way I open myself to a new song that is out there waiting to be found.”

Yet for all the acclaim, Stamets is still an outsider without a PhD or an academic or institutional sponsor. That has made it hard for his work to be taken seriously in some circles—“We are just weird enough that I t think we frighten people,” he says—but it’s an identity that he ultimately relishes. His inherently positive message—that we can tap a renewable natural resource to solve an array of environmental and medical challenges—has inspired a broad set of followers. Stamets leads workshops on “liberation mycology” and delivered the plenary a address at last year’s national botany conference. In February 2008, he held forth at the TED (Technology, Entertainment, Design) Conference, the annual conclave of deep thinkers and tech gurus in California. Afterward, Google’s founders “ambushed” him with an invitation to their exclusive summer think tank, and Al Gore complimented him on an obscure chemical reference, saying, “You taught me something I didn’t know about global warming.”

"NOT A SINGLE PROSPECT...was pleasing to the eye,” sneered Captain George Vancouver when he named this glacier-carved e labyrinth of channels and fjords Desolation Sound after spending a cloudy week here in the summer of 1792. But under n the clear July sky, it’s sublime: the water a deep, glassy blue, the islands dark green. Afternoon of the first day arrives without an agarikon sighting, so we head ashore to explore a patch of old growth. Stamets’s friends joke about his notorious “death is marches,” but the jaunt proceeds at the leisurely pace of a chanterelle foray. Fungi were among the first organisms al to colonize land 1 billion years ago, long before plants. A visitor to the planet 420 million years ago would have encountered y a landscape dominated by fungi such as prototaxites, a bizarre-looking, 30-foot-tall mushroom. Contemporary fungi may be more discreet, but they’re just as ubiquitous—and mysterious. Fewer than 7 percent of the estimated 1.5 million species have been cataloged. Mycologists have recently identified 1,200 species of mushrooms in just a few thousand square feet of Guyanese rainforest, half of them previously unknown to science.

As we walk, Stamets points out that the spongy feeling under our feet is a vast subterranean network of mycelium. Stamets refers to mycelium as “nature’s Internet,” a superhighway of information-sharing membranes that govern the flow of essential nutrients around an ecosystem. A honey mushroom mycelium that covers 2,200 acres in eastern Oregon is thought to be the world’s largest organism. When Stamets saw mycelium for the first time, growing like a spiderweb across a log, he brought it home and tacked it onto his bedroom wall. Mycelium’s labyrinthine tendrils pre- vent erosion, retain water, and break down dead plants into ingredients other organ- isms can use to make soil. Stamets likes to call fungi “soil magicians.”

Yet it can be difficult to champion an organism that grows out of poop or decaying wood, can be deceptively toxic, and appears extraterrestrial. Stamets says American society is pervaded by “mycophobia”—an irrational fear of fungi that he traces back to

England, whose medical tradition equates mushrooms with decay and decomposition. Stamets has little patience with those who disrespect mushrooms. “I hate the word ‘shrooms,’” he says. “Pet peeves: Don’t kick mushrooms in my presence and don’t use the word ‘shrooms.’”

The summer dry season has subdued the mushroom population, but as we walk and my mind becomes more focused they soon pop into view: bracket fungi growing like ledges across a fallen log, a fragile cup-capped mushroom camouflaged in leaf litter. Logging has razed the Pacific North- west’s old growth; less than 20 percent of the original forest is still standing. A handful of mushroom species, including agarikon, depends on this diverse habitat, whose dis- appearance Stamets views as not just a lost opportunity but a national security concern. The cancer drug Taxol was derived from the bark of Pacific yew trees, a conifer native to the Northwest. And tests of 18 of the 28 strains of agarikon Stamets has cultured have found varying levels of antiviral potency, indicating the great diversity even within a single fungus species, adding to the urgency of protecting its dwindling habitat. It’s conceivable that the most powerful strain is growing on a tree in a logging concession somewhere.

Foresters long assumed agarikon caused trees to rot, and preemptively logged them. Stamets, however, believes it actually protects trees from parasitic fungi. “The tree says, ‘I will accept you, Mr. Agarikon, but I want you to protect me. Give me life, and I will give you my body.’”

In the weeks before our cruise, the National Center for Natural Products Research identified the structures of the molecules responsible for agarikon’s antiviral properties. It found the molecules to be more active in the laboratory than the smallpox antiviral Cidofovir. Reverse engineering mushrooms’ complex chemical creations to synthesize a new drug is a slow and costly process; Stamets estimates that he’s sunk more than $400,000 of his own money into the effort. The next step toward developing a pharmaceutical is mammal studies, a gamble that the venture capitalists he has met with are so far unwilling to fund.

“I’ve seen the lab results. I know it has potential,” says Rasmussen of Instedd. “What I don’t know is how it performs in clinical trials. And that’s a deeply frustrating situation to be in—to see this level of activity against nasty bacteria and viruses and not have the ability to begin clinical trials and work up the scale to human trials and see what the most effective delivery meth- od is, what the dosing needs to be, what the side effects will be—and I think there will be very few. I mean, it’s a mushroom, for God’s sake.” Thus far, the active ingredients in agarikon show no or very little toxicity.

Stamets has long had a hunch that agarikon could be a pharmaceutical powerhouse. He knew from historic texts that other cultures had tapped into its medicinal properties. In the year 65, the Greek physician Dioscorides described it as a treatment for “consumption”—an early name for tuberculosis. A 19th century British text noted that it was still prescribed “to diminish bronchial secretion.” Agarikon was also highly valued by the Coast Salish First Nations peoples of British Columbia. The Haida of British Columbia’s Queen Charlotte Islands are said to have carved the tough, leathery fungus into spirit figures and placed them on the graves of shamans to protect them from evil spirits. Mushrooms also figure prominently in Haida mythology: Women, it is said, came into existence after a “Fungus Man” found shells that resembled vaginas. The Haida knew that boiling agarikon, which they called “ghost bread,” into a tea helped with lung problems.

Tragically, they never discovered what Stamets is now finding: that the mycelium running through the tree bark is resistant to smallpox, which decimated the Haida when the British brought the virus to the region in the late 1700s. A few years ago, Stamets visited the Haida Nation’s president. Oral traditions had kept the mush- room’s reputation alive, but its secrets had been forgotten. “I know my grandmother knew about this fungus,” the Haida leader told Stamets, “but after the smallpox epidemic we lost all of our elders, and we lost all of this knowledge.”

AS THE MISTY ISLES sails alongside East Redonda Island, all binoculars on deck look for snags—craggy treetops that indicate an old, decaying Douglas fir, agarikon’s ideal habitat. The captain, a Canadian named Mike, thinks we’d be interested in seeing some Haida pictographs on the northeast shore. The paintings come into view—crude red shapes on a granite face, sheltered by an overhang. Suddenly, from behind binoculars, a researcher yells, “There’s one!” Our attention pivots toward a dense cluster of trees about 100 feet to the left of the pictographs, where I can barely make out a white blob growing on a Douglas fir.

“Oh my, it’s huge!” Stamets cries. “It’s like the Moby Dick of agarikon...the big- gest one I’ve ever seen in my life! How cosmic, right where the pictographs are! God, you’re a beautiful column. It’s got to be 70, 100 years old.”

Mike anchors Misty and I ride to shore with Stamets in an inflatable boat. We walk to the base of the tree and gaze up at the agarikon, 20 feet off the ground. The fungus is two feet long and resembles a bloated, mutant caterpillar, tubular and segmented. It is growing around a stubby branch poking out from the tree. Stamets believes that it probably fell from higher up, accidentally landed on the branch, and then calcified the wood to provide itself with a sturdy perch—an unusual occurrence he’s never seen before.

From the pictograph site, someone calls out that one of the paintings appears to be of Fungus Man. “No way, no way!” Stamets exclaims. “Fungus Man is there? Oh boy, oh boy, I’m getting shivers up and down my spine now.” He takes three deep breaths. “We may have discovered a mystery that no one ever knew—that the pictographs exist here because of agarikon. I feel like this is a fulfillment of a dream. We’re so lucky. Unbelievable. See, this is the thing about mushrooms: It’s not luck. There’s something else going on here. We’ve been guided. But this is what happens. All of our big finds, we have been led.” It also happens to be Stamets’ 53rd birthday.

Stamets grabs a long stick and reaches up to poke the fungus. It won’t budge. He pokes again. “We really shouldn’t take it,” he concludes. “We should be honored that we found it. This is now super sacred.” He lets the agarikon be and walks over to check out the pictographs. Fading from time and the elements, the rock paintings depict a dolphin, a turtle, and a two-foot-high figure with stick arms, big round eyes, and what seems to be a mushroom cap growing out of its round head. Is it Fungus Man?

The afternoon sun is falling behind the island, so we leave the question unresolved and set Misty back on course. Just before dusk we reach the mouth of the Toba Inlet, a fjord carved into Canada’s mainland, flanked by high slopes of Douglas fir, red cedar, and al- der. We dock at a lone fishing lodge, and from an outdoor hot tub, we enjoy the tranquility that the salty George Vancouver once described as “an awful silence” pervading “the gloomy forest.” Captain Mike grills salmon and Stamets considers the day’s events. “I’m glad we didn’t take it,” he says. “When I had the stick in my hand, I felt, ‘Something doesn’t feel right about this.’ I thought, ‘If this is gonna come down just with a touch, I’ll take it. But if it gives me resistance, I’m stopping.’” (He returned the following month with a team of researchers to retrieve samples.)

Toward the end of our last day at sea, Misty turns down the east side of Cortes Island. Stamets spots another agarikon growing 35 feet above the water under the bottom branch of a Douglas fir, sweating beads of amber. He goes ashore for a closer look; while the fungus appears to be dead, he believes the mycelium running up the tree is still alive. Climbing onto an over- hanging rock, he finds another one growing in a tree, a sign of an old colony.

Back on deck, Stamets looks across the open water. “How is history going to re- member you?” he wonders. “How is Fleming remembered? How are people who have saved millions of lives remembered? I want to die with a smile on my face.” He then strips off his clothes and dives into Desolation Sound.

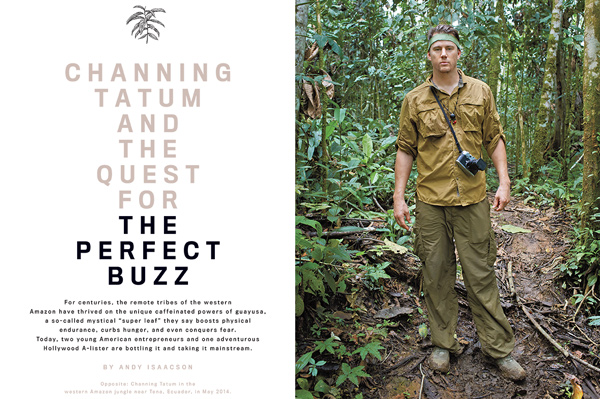

Channing Tatum and the Quest for the Perfect Buzz

MEN'S FITNESS | How two young entrepreneurs and one Hollywood A-Lister, with the help of a caffeinated Amazonian “super leaf,” are trying to shake up the $30 billion energy-drink market with a healthier alternative.

FIRST PUBLISHED IN MEN'S FITNESS, MARCH 2015

CHANNING TATUM HAS A RECURRING DREAM in which he sprints furiously across an unfamiliar landscape, then, arms outstretched, takes flight, soaring above the terrain like a hang glider. A version of this dream comes to him one night in spring of 2014, while dozing in a hammock deep inside Ecuador’s rainforest. This time he runs up a hill dotted with tall trees. At the crest stands a forbidding wall that rises as he draws nearer. Barefoot, he bounds up the wall and, reaching the top, sees a vast territory unfurling toward the horizon. He pauses, then plunges down the other side.

The next morning Tatum recounts the details of the dream to a group of us sitting on tree stumps around a smoldering fire, in a remote indigenous Sápara settlement near the border of Peru. The villagers have painted our cheeks with a reddish pigment made from tree seeds, issued us each Sápara names (Tatum takes “Tsamaraw,” which means “protector spirit”), and blown tobacco smoke into our faces to expel negative energy.

In our hands are coconut shells that contain a caffeinated elixir we’ve traveled 4,000 miles to find: guayusa, a plant native to the western Amazon, whose green, elliptical leaves have been a staple of the region’s indigenous populations for thousands of years.

The Sápara drink guayusa (“gwhy-YOU-sa”) for stamina, and as a tool to interpret dreams. Shipibo medicine men in Peru prescribe a strong, guayusa-based drink to patients who suffer from trauma, as a way to conquer fear. The Kichwa people, in Ecuador’s northern jungle, say the plant also kills hunger, and often pack guayusa leaves as their only sustenance on long hunting expeditions.

A Kichwa man had described to me the mystical circumstances surrounding the discovery of the plant’s energy-boosting properties. It was during an era of tribal warfare; one night the spirit of a tree told a sleeping Kichwa sentinel, “Hey friend, I can help you.” The sentinel awoke to find a bush rustling nearby. He chewed its leaves, and immediately felt alert and animated. Today the Kichwa refer to guayusa as “the night watchman’s plant.”

Tatum, the star of Foxcatcher and this summer’s Magic Mike XXL, has come to the Amazon to sample the plant for a different reason. An investor in the New York-based beverage startup Runa (a Kichwa word meaning “fully alive”), the first company to produce drinks containing guayusa, he wants to learn everything there is to know about it. We’ve spent the last few days with Runa’s co-founders, Tyler Gage and Dan MacCombie, drinking, farming, and literally bathing in guayusa as women pour bucketfuls over our heads.

Gage and MacCombie represent the latest entrepreneurial rush into the rainforest—a place from which, in recent years, marketers have emerged with billion-dollar beverage products like açai. Leveraging Tatum’s celebrity, the pair hope to break into the $30 billion energy drink market, a field dominated by Red Bull and brands like Monster Beverage, which has concocted a juggernaut out of guarana, another caffeinated Amazonian plant. Trouble is, unlike guarana, few people have heard of guayusa. Tatum, Runa’s unofficial spokesman (his exact role is still being hashed out), hopes to change that.

After Tatum finishes describing his dream, a soft-spoken Sápara man focuses on him: “Your running represents the instinct of always striving to go further,” he says. “By making it to the top, you made it in your personal, professional, and spiritual life—there is nowhere else to go. But that expanse on the other side: That is the platform to recognize who you truly are.”

I wait for Tatum to lighten the mood. After all, this is the Jump Street star whose dick jokes have gone viral. He’s also a well-known prankster off camera. In fact, earlier this trip, he yanked me from a raft into a fast-flowing river and goaded me into eating a squirming grub from a palm tree. I expect him to respond to this shamanic psychoanalysis with a self-deprecating joke.

Instead Tatum nods along earnestly, pauses, then takes a sip from his coconut shell and launches into yet another dream, about waking up in a room from which he can’t escape. “This happens a lot,” he begins, “and I wonder what it means...”

The day before, at Runa’s factory in Archidona, Ecuador, Gage, MacCombie, Tatum, and his producing partner, Reid Carolin, take a tour of the company’s guayusa factory. Inside a low-slung white building covered in plastic, a woman in hospital scrubs and a surgical mask stirs beds of leaves, allowing them to dry and oxidize. They smell pleasant, like freshly cut grass, and Tatum snatches a pile and burrows his nose in it. He and Carolin first discovered Runa at a Whole Foods in New Orleans while shooting 21 Jump Street, in 2011, and the drink became their lifeblood as they raced to finish the Magic Mike script. “We were hammering it like it was a drug,” says Tatum. “Runa went in smooth and left smooth, and gave a longer buzz than coffee.” He now starts every day with a can of it. The next morning, I watch as he slams one then backflips off a 50-foot bridge into a river.

An 8.4-oz can of Runa’s energy drink comes in two flavors: Berry, with 17 grams of sugar, and Original Zero, a sugar-free version. Both have 120 milligrams of caffeine from guayusa leaves, which are dried in Archidona, shipped to a facility in New Jersey, then brewed into the carbonated energy drinks as well as a line of glass-bottled teas flavored with mint, hibiscus, and lemongrass.

Before Gage and MacCombie launched their company, not a single scientific paper had been written about guayusa. The Kichwa people say the plant can replace food on lengthy jungle trips. Both Gage and Tatum say that after drinking guayusa, they feel a pleasant boost without the jitters coffee gives them. “I needed something that gave me a longer burn and didn’t leave me cracked out,” says Tatum. Gage recalls a curious sensation the first time he drank guayusa. “I felt very awake but rooted at the same time,” he says. “I wasn’t sure why, but it was striking to me.”

Recent research conducted by Applied Food Sciences, a U.S. supplement firm that plans to market guayusa extract, offers evidence to support the “slow burn” claim. The plant is part of the holly family, and appears to offer the virtues of both tea and coffee: Its leaves contain significant levels of various antioxidants, including the catechins found in green tea, which reputedly fight cancer and boost metabolism, and the chlorogenic acid in unroasted coffee beans, which spurs weight loss by slowing the uptake of glucose from the intestines.

In addition to natural caffeine, guayusa also contains theobromine, a stimulant abundant in chocolate. Ounce for ounce, there’s less caffeine in guayusa than in dark roast coffee, but for reasons not yet well understood—having to do with the synergistic effects of these various compounds—the body metabolizes the caffeine in guayusa over a longer period of time.

“For endurance athletes who’d like to have more of a sustained release if they’re doing something more than a quick run—this really helps for that,” says Chris Fields, vice president of scientific affairs at Applied Food Sciences, which is starting clinical trials to investigate guayusa. “It’s a really unique plant, and now we seem to understand why it’s been used for centuries by Amazonian groups—it has so many medicinal benefits.”

Guayusa lacks tannins, the compounds in green and black tea that give it its bitter, puckery quality. When I drink a 14-oz bottle of Guavo Zero Unsweetened Runa, it tastes like watered-down tea. The first thing I notice sipping an 8.4-oz can of Runa Original Zero (with a hint of lime) is a sharp acidic tinge of artificial lime that instantly dissolves into a leafy, tea-ish aftertaste. The fizzy, one- two punch reminds me more of a store-bought Arnold Palmer than it does a syrupy Red Bull. (This is not a bad thing.)

Guayusa’s energy kick is gradual, more tortoise than hare. After one serving, I feel a subtle caffeine lift, rather than a spike. (For those who rely on the jolt of a Grande Pike Place or Monster, take note.) Two servings later, though, my body feels alert, and I’m humming along like a machine. I can see why Tatum and Carolin drink it during script-writing marathons. “The whole reason we [embraced Runa],” says Carolin, “was because we saw the effect this product had on our creativity.”

By offering a product with this unique rush, and by touting its claim of clean energy, Runa hopes to muscle into a marketplace cluttered with less healthy choices. The definition of “energy drinks” is somewhat elastic—they’re marketed as dietary supplements—but all tend to share large doses of caffeine combined with taurine, glucuronolactone, carnitine, B vitamins, and ginseng, various forms of stimulants, which, in excess, can give rise to harmful side effects. Most energy drinks also pack lots of sugar. An 8.4-oz can of non- diet Red Bull has nearly seven teaspoons of added sugar. (The American Heart Association advises no more than nine teaspoons of added sugar a day for men.)

Though the health effects of all the various chemical and herbal ingredients used in energy drinks and their possible interactions with caffeine are largely untested, the consequences of excess caffeine consumption are well understood: tachycardia, arrhythmia, hypertension, seizures, insomnia, and anxiety. According to the Center for Science in the Public Interest, a health advocacy group, FDA documents show that in the past decade, 34 deaths have been linked to, and possibly caused by, energy drinks. “Energy drinks are clearly causing symptomatic arrhythmias,” says Stacy Fisher, M.D., director of complex heart diseases at University of Maryland School of Medicine. Market research firm Mintel reported last year that nearly six in 10 Americans who consume energy drinks or shots—mostly 18– to 24-year-olds—say they now worry about their health.

“Right now, our low-hanging fruit is reluctant Red Bull drinkers who are like, ‘I drink this stuff but I know I shouldn’t, I know there’s something better’—which I think is a huge audience,” Gage says. “We just need to communicate in the right way to get them.”

Guayusa had never been grown commercially until five years ago, when Gage and MacCombie, two friends from Brown University, began shipping bags of the leaves to the U.S. Today Runa is sold in 7,000 stores across the country, including Safeway, Whole Foods, and Vitamin Shoppe. Last year, the company took in $2 million in sales; this year it’s on track to make $8 million. Runa has also attracted an eclectic mix of investors, including responsAbility, a Swiss sustainable management fund; a successful musician and producer named Dr. Luke; and the founder of Zico coconut water, Mark Rampolla.

Another investor, New York artist Neil Grayson, who’s a friend of Tatum’s and knew of the actor’s taste for Runa, connected him with Gage in 2013. Tatum immediately noted an auspicious coincidence: The character he’d played in his 2006 breakout film Step Up was also named Tyler Gage. If for no other reason, he tells me, “the sheer sake of weirdness” piqued his business interest in Runa.

Gage first tasted guayusa in 2005, after his freshman year in college, when he was in Costa Rica doing research with an American ethnobotanist. At the time, Gage, who’d been recruited to play soccer at Brown, was obsessed with health, nutrition, and peak performance. He’d tried going vegan for 18 months and Paleo for a spell, and even experimented with lucid dreaming. “I was interested in what the human mind has the capacity to do,” he says.

Eventually Gage came upon books by a decorated triathlete named Mark Allen, who’d studied the teachings of a Huichol shaman from Mexico. “He was relatable to me, from an athletic performance point of view,” says Gage, who reached out to Allen after his freshman year. “This wasn’t a dude who believes in spirits and wooah. No—homie won the freaking Ironman six times, and he attributes his success to the strength he learned with shamanism.”

Gage studied with Allen, who inspired him to study plant medicine in the Peruvian Amazon. There, for college credit, Gage researched the ethnolinguistics of the Shipibo people, while the Shipibo shamans put him through intensive ceremonies and diets. “Every day I had to get up at sunrise, drink these gnarly plants, and basically sit out in the jungle by myself,” he says. “It was really intense and really cool. And I can’t really explain it, but that’s when I remember feeling things shifted inside me.”

When Gage got back to Brown, his friend MacCombie was enrolling in a class on social entrepreneurship; he dragged Gage along. The course required that they write a business plan. In Peru, Gage had seen how Amazonian communities are often drawn into business with oil and logging companies for lack of any economic alternatives, so the two conceived of a company selling a guayusa-based beverage. As far as they were concerned, it was a class exercise. But their professor—an entrepreneur named Danny Warshay, who’d worked for Duncan Hines—urged them to think otherwise. “It hadn’t even crossed our minds,” Gage confesses. Over late nights, however, the idea marinated. In December 2008, two days after he and MacCombie graduated, they flew to Ecuador.

After six months of backpacking among villages to secure guayusa suppliers, Gage and MacCombie landed a $50,000 small business grant from Ecuador’s Ministry of Export, which in 2010 they used to build Runa’s first research facility, a steel drying-chamber in a bamboo garage full of chickens. Larger grants from the Ecuadorean government and the U.S. Agency for International Development allowed them to build the first real Runa factory. They shipped guayusa back to the States and managed to sell the first boxes to Whole Foods. At a natural foods trade show in 2011, Gage and MacCombie were hawking samples of their “Amazonian tea” from a remote corner booth when Neil Kimberley, former brand director at Snapple, happened by and offered to help formulate their product. “You guys seem pretty cool,” he told them. “Give me a call.” He’s now on Runa’s board of advisors.

Today, Runa’s harvest comes from over 3,000 local farmers, who tend the bushy plant in traditional gardens called chakras. The company’s also launched a nonprofit that funds the largest reforestation program in the Ecuadorian Amazon, partly supported by the MacArthur Foundation, and is also helping guayusa farmers form cooperatives.

We’re sitting on a grassy airstrip beside another Sápara settlement when Gage reaches into a cardboard box and pulls out a few prototypes of the Runa energy drink can, which prominently features a guayusa leaf and the words “Clean Energy.” One of Runa’s investors, Kim Jeffery, who, as the president and CEO of Nestlé Waters North America, had helped turn it into the continent’s third-largest beverage company, has advised Gage on the importance of a clear, succinct message. “His thing is: You have three seconds to tell people what your product is,” Gage says. “What we want people to say about Runa is not that it’s tea, or light tea, but that it’s better than tea. Categorically better, and categorically different.”

Tatum doubts whether the can’s current design accomplishes that. “One thing Red Bull has done really well is that it can be sitting all the way over there, even in the dark, and you know exactly what it is,” he says, pointing across the runway. “Just, bang—I know it. So, the leaf: I know that’s what it is. But is that what we’re advertising? What are we trying to get people to understand? The biggest thing for me is to figure out how to key into exactly what it should be used for and what it’s going to deliver. It’s alive. It sharpens you. It gives you insight into your world—focused presence, not just jacked up. The packaging should say what it’s going to do for you. Then if people wonder what it’s made from, they’ll turn it over and read the ingredients and find out it’s natural and it’s made from a leaf in South America.”

Carolin adds, “I think people want to feel like they’re holding a symbol in their hand, and that’s what Red Bull has become.”

“You’ve got to make it cool to drink,” says Tatum. “I hate to be some kind of idiot American saying that, but look—you can’t deny the product. It makes you run faster, jump higher. Now you just have to—.”

“Put the ‘swoosh’ on it,” Carolin says. “Yes!” insists Tatum. “That thing that says: This is why it’s fucking cool.” Gage, for his part, wants people to think of Runa as an alternative to Red Bull in a way that some now see Vita Coca—the country’s top-selling coconut water brand—as a replacement for Gatorade. His challenge is to distinguish guayusa from tea, and somehow make it hip. “This is 99% of what’s going to determine if we’re a $10 million company or a $500 million company,” says Gage.

Yet he recognizes this is all nearly impossible without someone like Channing Tatum. In 2011, Vita Coco, whose celebrity investors include Madonna and Rihanna, ran a billboard campaign that featured Rihanna urging consumers to “Hydrate naturally from a tree, not a lab”—a jab at Gatorade and Powerade. That year the company saw its revenue double to nearly $100 million.

To date, Runa’s celebrity weaponry has been small gauge. The company sends products to a “Runa Tribe” made up of athletes like wakeboard world champion Darin Shapiro and pro kiteboarder Damien LeRoy—“individuals who embody what it means to be Runa,” according to the company’s website—hoping they’ll spread the gospel. But the star power of Tatum, Runa’s unofficial pitchman—he’s discussing with the company various ways they might leverage his celebrity—actually has the potential to blast the brand into the mainstream. “We’re dealing with guys [Tatum and Carolin] whose entire professional business is public entertainment, and what’s cool and sexy. And they’ve been successful at that. Channing has his finger on the pulse of the average American: what they do, how they think, and what they want.”

A few weeks after returning from the Amazon, Tatum, in preparation for Magic Mike XXL, begins a 10-week regimen with celebrity trainer Arin Babaian to mold his body back into male stripper form—workouts fueled by guayusa. “We buy into things we believe in, and this is something I can completely get behind,” he says on our way back from Ecuador. “Someone can just be like, ‘Oh, you’re just getting paid for this, right?’ and I can say, ‘No, I actually just drink the shit out of it.’” ■

Deep Impact: Attenborough at 88

AUDUBON | Never mind old age. David Attenborough still does his own stunts in a lifelong quest to bring wildlife to your living room (or mobile device).

FIRST PUBLISHED IN AUDUBON, JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2015

DAVID ATTENBOROUGH MAY BE 88 years old, but you will not find him eating green Jell-O on a Barcalounger. Recently, the octogenarian was braving minus-40-degree weather in Antarctica one day and piloting a glider alongside a digitally rendered pterosaur on another. “Rather more fun than sitting in the corner slobbering, isn’t it?” he teased last June at Wicken Fen National Nature Reserve, near Cambridge, where I found him filming scenes for Conquest of the Skies, a three-part series in 3D about the evolution of flight.

For more than 60 years—in black and white, color, HD, and, recently, 3D—the legendary broadcaster has introduced millions of people to bowerbird courtship displays, lyrebird mimicry calls, and countless other amazing wonders of the natural world. In Britain, where he lives, Attenborough was recently voted the most trusted figure, in a public poll, and is widely considered the “greatest living national treasure.” (He’s also an extinct treasure: A Mesozoic reptile, Attenborosaurus, bears his name.)

Wicken Fen’s meadows and sedge beds make up one of the most species-rich habitats in Britain, and offered an ideal setting for filming dragonflies. Attenborough lay on the grassy bank of a canal beside a foot-long fossil cast of a griffinfly, a giant dragonfly-like predator that conquered the skies during the Carboniferous Period. The sky above was cloudless and warm, and Attenborough wore his signature blue, short-sleeve collared shirt and khaki slacks, in the fashion of a gentleman naturalist.

As the crew from Atlantic Productions aligned the 3D cameras, Attenborough ran a comb through his thick silver hair. By his nature—and that of his work—Attenborough is not one to rely on hair and makeup people. A couple of months earlier, in Borneo, he had gamely offered to hang from a rope 250 feet high inside the Gomantong Caves as a million bats flew past him on a feeding exodus. In Scotland he took part in a high-speed boat chase down a loch with a flock of swans.

“I joke that Daniel Craig always does his own stunts for Bond, and, well, David does his own, too,” said Anthony Geffen, the series producer. “He doesn’t want someone else to.”

When David Attenborough speaks, it is in a soothing, melodic voice that can take the form of an enthusiastic whisper. “Let me tell you, when you’re sitting next to a gorilla, you don’t shout,” he told me.

This day at Wicken Fen, murmuring to himself, Attenborough rehearsed the lines he’d prepared for his “piece to camera,” the classic field bit he is sometimes known to utter while short of breath. Attenborough carefully scripts each program himself, leaning on scientific papers and various specialists, but will often tweak the wording of a line right up until the shot. “He’s careful not to exaggerate things, because then you quickly run out of platitudes—he lets the stories be told by the creatures around him,” Geffen said. “But often he will highlight an extraordinary thing, or he’ll just suddenly think, ‘Well, isn’t that just a better way into the story.’

The director, David Lee, called for quiet. “Are we ready? And . . . action!”

Attenborough began slowly in his distinctive cadence, as if lecturing to a class of undergraduates. “This is a cast of the oldest fossilized wing yet discovered,” he said to the camera, which was affixed to a 10-foot crane. “As you can see, it looks very like that of a dragonfly. Except that it is . . . gigantic.”

Take two. James Manister, a scientist working with the production company, pointed out that the fossil was in fact the oldest “complete” wing fragment. Attenborough started in again. “It was found in rocks dating from 290 million years ago, in North America. And its owner must have had a wingspan of around 60 centimeters.”

With dramatic flair, he scrunched his face: “It was a monster.”

Even Americans who might reach for the name David Attenborough—“Is that the Planet Earth guy?”—would easily recognize his voice, which has pretty much become synonymous with natural history television. (It has also lent itself to self-parody; Attenborough fans will enjoy the mock narration he did last year, for BBC Radio 1, of a Great Britain-U.S. women’s Olympic curling event: “Off she goes, gently but flamboyantly launching the oversized walnut down the frozen river . . .”)

Across his astonishing career, Attenborough has written, narrated, or appeared in more than 100 programs. Taken together, they amount to an unabridged survey of life on earth—from the planet’s origins to its polar habitats to insects to birds to evolution. But Attenborough’s earliest interest was fossils.

As a child he kept a museum of stones and fossils in his family’s home in Leicester. At 13, purportedly without his parents’ knowledge, he bicycled alone for three weeks to the Lake District and back, on a collecting trip. In grammar school he read about the journeys of the 19th century British naturalists; at 14, he once said, he thought “that the only thing any decent, red-blooded male could want to do in life is climb Everest.” (He has trekked around the north and south poles, and many places in between, but alas, never to the world’s highest peak.) Attenborough went on to study natural sciences at Cambridge but realized he was not cut out to be a scientist. At 26, after a two-year stint in the Royal Navy followed by a spell editing children’s science textbooks, he landed his first job as a BBC producer.

Back then, animal TV programs consisted of a London Zoo employee, under glaring studio lights, describing an animal that he’d plucked from its cage. “These poor creatures looked like oddities—I mean, they looked like freaks,” Attenborough told an audience in 2011. “I thought, why can’t we show the animals in the wild?” Sixteen-millimeter film limited the quality of pictures taken inside a dark rainforest, but Attenborough figured that the BBC could at least film zoo people trapping the wild animals and then describe them later in a studio. Zoo Quest, which pioneered on-location wildlife filmmaking, began in Sierra Leone, where the crew, including Attenborough as the sound recorder, captured a White-necked Rockfowl. When the zoo employee fell sick, Attenborough pinch-hit in the presenter role: In Guyana, he got a close-up with some anteaters; in New Guinea, Zoo Quest was the first to capture a bird of paradise display in the wild. Recalling this a few years ago, Attenborough said: “I thought, what a racket. Wow, if I can play my cards right, I can get away again.”

Today there are few corners of the planet where David Attenborough hasn’t traveled—on his programs, he’s fond of beginning a sentence on one continent and completing it on another—although he’s as happy at his Richmond home, on the outskirts of London, gazing at the ducks and rare plants in his garden pond. Since Jane, his wife of nearly 40 years, died in 1997 of a brain hemorrhage, Attenborough has lived there with his daughter amid displays of fossils, aboriginal art, and books on many subjects. He doesn’t think of himself as a savvy socializer (“I’m not very good at cocktail parties,” he’s said) or a misanthrope (“I’m not obsessed by the natural world to the exclusion of human beings,” he told me). However, there is one human issue that keeps him up at night: Population growth—the world’s numbers have tripled since Attenborough started making programs. He’s affiliated with Population Matters, a U.K.-based think tank, and is outspoken on the issue: “I believe that almost every ill that afflicts the world today can be put down to increasing population size,” he said.

After getting a pacemaker in 2013, Attenborough (seen here in Borneo) said, "I've been broadcasting for 60 years. I don't want to slow down. Retirement would be so boring." Photo: Credit: Colossus Productions

At Wicken Fen, while the cameramen set up another shot on a footbridge by the visitors center, Attenborough sat quietly by himself in a lawn chair under a canopy. He’s still spry, but as he ambled around, slightly hunched and swaying, his body resembled an aging elephant. At his feet rested a black Samsonite briefcase stickered with “DA,” which contained The Times, a handwritten address book, and an outmoded cell phone.

The next scene on the bridge (ultimately scrapped from the film) involved Attenborough describing a prehistoric dragonfly on the railing that would be rendered using computer-generated imagery. Since the mid-1960s, when he ran BBC Two and oversaw the introduction of color television, Attenborough has kept apace with technological advances as a means to tell better, current, unseen stories. For Conquest of the Skies, he wondered at the outset how the producers could get cameras in the air to simulate a true bird’s-eye view. Atlantic Productions then developed, from scratch, a 3D “octocopter” that holds two cameras side by side, which it says is the first of its kind. “He’s not a gadget king, but I’m constantly talking to him about new technology, and he loves it,” said Geffen, who has made 10 programs with Attenborough, including Micro Monsters 3D, which used fiber-optic cameras. Their next project, about the Great Barrier Reef, will employ satellite photography and cutting-edge underwater cameras. “He’s like a kid,” Geffen said. “ ‘What can it do, let’s have a look at it.’ ”

Take one. Attenborough reached the empty spot on the railing and looked to the camera: “How is it that these ancient dragonflies grew to be that size, whereas no dragonfly today can?” he asked. “The answer seems to be with the air. Or, rather, the amount of oxygen that’s in the air.”

Attenborough’s great talent is in distilling the stuff of lengthy scientific papers into pithy, descriptive sound bites, and telling stories that manage to feel fresh despite the fact that we’ve all seen countless clips of hummingbirds and coral reefs. In Britain, Attenborough programs draw on a certain national nostalgia, but it’s nevertheless remarkable that an 88-year-old in grandpa pants has managed to stay relevant—and as popular as ever—in the age of Finding Bigfoot and Pit Bulls and Parolees (two Animal Planet hits).

The director called for another take. Excusing himself for a moment, Attenborough walked behind the camera and pulled a field guide out of his briefcase.

“Classic David,” remarked Geffen. “This is going across the world, and he wants to make damn sure it’s right.”

In a Changing Antarctica, Some Penguins Thrive as Others Suffer

NEW YORK TIMES | Global warming and the Adélie penguin.

FIRST PUBLISHED IN THE NEW YORK TIMES, MAY 9, 2011

ROSS ISLAND, ANTARCTICA— Cape Royds, home to the southernmost colony of penguins in the world, is a rocky promontory overlaid with dirty ice and the stench of pinkish guano. Beyond the croaking din of chicks pestering parents for regurgitated krill lies the Ross Sea, a southern extension of the Pacific Ocean that harbors more than one third of the world’s Adélie penguin population and a quarter of all emperor penguins, and which may be the last remaining intact marine ecosystem on Earth.

The penguin colony is one of the longest-studied in the world. Data on its resident Adélie penguins was first acquired during the 1907-9 expedition of Ernest Shackleton, the eminent British explorer, whose wooden hut stands preserved nearby. “This is penguin nirvana,” David Ainley, an ecologist with the consulting firm H. T. Harvey and Associates who has been studying Ross Sea penguins for 40 years, said on a morning in January. “This is where you want to be if you’re a pack ice penguin.”

Of the species that stand to be most affected by global warming, the most obvious are the ones that rely on ice to live. Adélie penguins are a bellwether of climate change, and at the northern fringe of Antarctica, in the Antarctic Peninsula, their colonies have collapsed as an intrusion of warmer seawater shortens the annual winter sea ice season.

In the past three decades, the Adélie population on the peninsula, northeast of the Ross Sea, has fallen by almost 90 percent. The peninsula’s only emperor colony is now extinct. The mean winter air temperature of the Western Antarctic Peninsula, one of the most rapidly warming areas on the planet, has risen 10.8 degrees Fahrenheit in the past half-century, delivering more snowfall that buries the rocks the Adélie penguins return to each spring to nest — and favoring penguins that can survive without ice and breed later, like gentoos, whose numbers have surged by 14,000 percent.

The warmer climate on the Antarctic Peninsula has also upended the food chain, killing off the phytoplankton that grow under ice floes and the krill, a staple of the penguin diet, that eat them, by as much as 80 percent, according to a new study published this month in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

But in the Ross Sea a reverse trend is occurring: Winter sea ice cover is growing, and Adélie populations are actually thriving. The Cape Royds colony grew more than 10 percent every year, until 2001, when an iceberg roughly the size of Jamaica calved off the Ross Sea ice shelf and forced residents to move 70 kilometers north to find open water. (The iceberg broke up in 2006, and the colony of 1,400 breeding pairs is now recovering robustly.) Across Ross Island, the Adélie colony at Cape Crozier — one of the largest known, with an estimated 230,000 breeding pairs — has increased by about 20 percent.

Climate change has created a paradise for some pack ice penguin colonies and a purgatory for others, but the long-term fate of all Adélie and emperor penguins seems sealed, as relentless warming eventually pulls their rug of sea ice out from under them. Some scientists attribute the recent sea ice growth in the Ross Sea to the persistent ozone hole, a legacy of the human use of chlorofluorocarbons that cools the upper atmosphere over the continent, increasing the temperature difference with the lower atmosphere and equator, and over the last 30 years has delivered significantly brisker westerly winds in the summer and autumn. The warming of Earth’s middle latitudes is having a similar effect, increasing that temperature difference and sending stronger winds that push sea ice off the coast and expose pockets of open water, called polynyas, that give nesting Adélie penguins easier access to food.

Meanwhile, consumers’ appetite for Chilean sea bass (Antarctic and Patagonian toothfish) may also be benefiting Ross Sea penguins, as fishing fleets from southern nations converge on one of the last remaining refuges of the fish (Dissostichus mawsoni). A fishery in the Ross Sea that opened in 1996 and was certified sustainable in December by the Marine Stewardship Council, could ultimately serve Adélie penguins by reducing competition for Antarctic silverfish (Pleuragramma antarcticum), a sardine-size fish that the penguins and toothfish enjoy. Dr. Ainley and colleagues have reported seeing fewer killer whales in the southern Ross Sea since 2002. The whales feed on toothfish, and fewer sightings suggest that the fishery is already altering the ecosystem.

Researchers witnessed Ross Sea penguin colonies thrive during the 1970s when commercial whaling removed 20,000 Antarctic minke whales, also a food competitor of Adélies, from the penguins’ wintering area. Adélie populations eventually leveled off after 1986, after an international moratorium on whaling began (and remained static until the more recent influences of climate change). Japanese whaling of minkes resumed right after the moratorium was instituted, purportedly for science, a claim that conservation groups dispute and that has incited a confrontation in the Ross Sea between the Japanese fleet and the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, an antiwhaling vigilante group.

“It has become difficult to separate whether the increase is due to climate change or fewer toothfish,” Dr. Ainley said. “Both factors seem to be working at the same time.”

On a chilly morning in January, the Cape Royds colony was clustered across the dark volcanic rock in crèches: month-old chicks, furry and pear-shaped with tummies full of krill, huddled near their parents as adolescent penguins, still too young to breed, acted “like teenagers trying to figure out the social scene,” in Dr. Ainley’s assessment. Their cuddly appearance is misleading, it turns out, a projection of human sentiment. “They’re really nasty to one another,” Dr. Ainley said, “and if you try to pick one up you’ll have your hands full.”

Climate models predict that the winds and sea ice will continue to increase in the Ross Sea for the next 30 to 40 years, at which time the region is expected to experience a tipping point, as rising temperatures and the waning effect of the ozone hole, now getting smaller, transform the climate into the kind now seen in the Antarctic Peninsula.

Already, that process is under way. The average summer temperature at McMurdo Station, the American research base on Ross Island, has inched up 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit in the past 30 years, records show, more than the global average. Scientists conducting longterm studies of lakes in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica’s largest ice-free area, report that after a decade of cooling, some lakes in the Taylor Valley are now gaining heat. During this past research season the scientists recorded unprecedented lake levels caused by higher glacial runoff.

On Beaufort Island, north of Ross Island, glaciers have retreated over the rocky coastline farther than they have in 30,000 years, scientists estimate, a time before the last ice age. The receding ice has opened up more nesting habitat for the resident Adélie penguin colony, which has expanded to 55,000 breeding pairs from 40,000 in the last decade.

As the sea ice retreats, researchers expect that Adélie penguins living in the Ross Sea will be forced to shift their range farther south toward the pole. In a study between 2003 and 2005, Dr. Ainley and colleagues from PRBO Conservation Science, Stanford University, NASA and the British Antarctic Survey used geolocation sensor tags to track penguins from Cape Royds and Cape Crozier to better understand their migration patterns. Published last year in the journal Ecology, the study revealed how the penguins depart their nesting grounds in February, at the end of the austral summer, and head north on foot and ice floes to flee the protracted darkness of the Antarctic winter. They appear to stop on the sea ice about 300 miles from the boundary with open water, where they stay to forage and fatten before doubling back south to their island breeding sites ahead of the creeping northern night — an 8,000-mile journey.

By carbon-dating mummified penguin remains, researchers have been able to construct a long-term history of the Adélie in Antarctica, indicating that throughout the last ice age penguins changed their migration routes and colony locations in response to advances and retreats of the sea ice. However, their range appears to have never extended farther south of where it is currently, for the simple reason that Adélie penguins appear to need light — if only twilight — to forage and navigate, and as comfort against predators.

“Emperor and Adélie penguins have an obligatory association with sea ice,” Dr. Ainley said. “As the sea ice goes, these species will go.” The Ross Sea is projected to be the last place on Earth where sea ice will endure. But as the annual winter sea ice boundary retreats farther south, pack ice penguins may ultimately find themselves trapped behind a curtain of polar night for which they have no hardwired strategy.

Indeed, Dr. Ainley speculates, Adélie penguins face possible extinction not merely by a loss of habitat — but by an unshakable fear of darkness.